The Saddest and Strangest Tales of Animals in Space

From spiders struggling to make webs in orbit to bats clinging to the outside of the Space Shuttle, the history of animals in space is as fascinating as it is weird. Here are some of our favorite stories.

On June 11, 1948, a rhesus monkey named Albert I become the first animal to reach space, strapped aboard a V-2 Blossom rocket that flew to a suborbital height of 83 miles (134 kilometers) above the surface. Since then, scientists have sent a dizzying assortment of living organisms to space, including dogs, apes, reptiles, insects, plants, and various microorganisms. Many animals were killed as a result of these pioneering missions. As NASA has said, they “gave their lives…in the name of technological advancement, paving the way for humanity’s many forays into space.”

This story was originally published on August 4, 2022.

The Soviet Union sent its fair share of dogs to space during the formative years of the country’s space program, including Laika—the first animal ever sent to Earth orbit. Laika died during this one-way mission. These experiments were crude by today’s standards, as Laika, among other Soviet dogs sent to space, were literally stray mutts picked off the street.

Prior to the 1957 Laika mission, the Soviet Union conducted a number of high-altitude tests with canines. In 1951, a dog named Smelaya ran away a day before the scheduled launch, leading to concerns that she might get eaten by wolves living nearby, according to NASA’s “A Brief History of Animals in Space.” Smelaya managed to return the next day, and the test flight proved to be a success. Later that same year, a dog named Bobik also escaped, never to return. Unfazed, the mission planners found a replacement hanging out near a local pub; the team named her ZIB—the Russian acronym for “Substitute for Missing Dog Bobik.” It’s the classic story of hanging out at a bar one day and then finding yourself launched to a suborbital height of 60 miles (100 kilometers) the next.

The first mice to reach space did so in the 1950s, but these early missions often ended in disaster. In 1959, the U.S. Air Force scrubbed a launch attempt from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California when sensors failed to detect signs of life in the Discoverer 3 capsule. The four mice were found dead, having overdosed on the krylon paint sprayed onto their cages to cover the rough edges. The mice had evidently found the krylon to be tastier—and deadlier—than the formula provided to them.

A second launch attempt with a back-up mouse crew was also scrubbed when sensors recorded 100% humidity inside the capsule. “The capsule was opened up and it was discovered that the sensor was located underneath one of the mouse cages,” according to NASA. The sensor was “unable to distinguish the difference between water and mouse urine,” and the launch proceeded after it dried out, according to the space agency. The rocket finally managed to blast off on June 3, but the rocket’s upper stage fired downward, sending the vehicle—along with the four mice—crashing into the Pacific Ocean. Clearly, it was a mission that simply wasn’t meant to be.

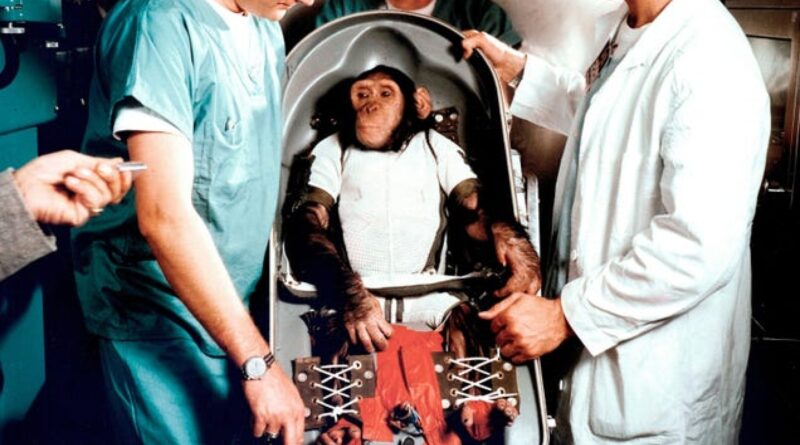

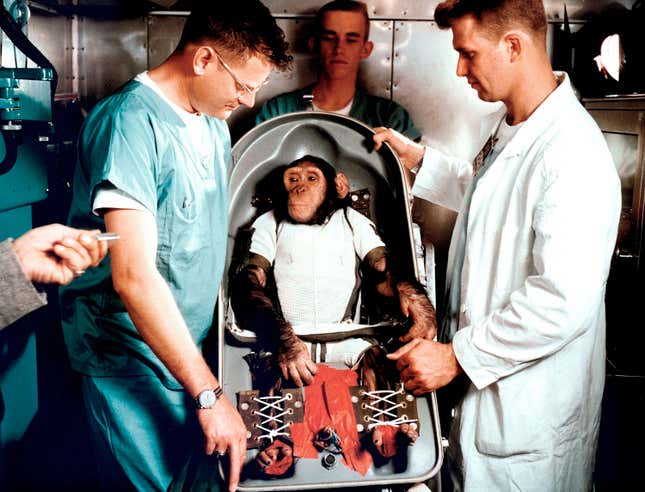

Ham the chimpanzee is famous for being the first great ape in space, earning this distinction on January 31, 1961. A key goal of this NASA Mercury-Redstone mission was to determine if animals could perform tasks in space. To that end, Ham, who was only 2 years old when the training began, was taught to move levers, both to receive awards in the form of banana pellets and to avoid punishment in the form of electric shocks to his feet. Ham, in addition to dealing with the terrifying demands of spaceflight, also had to actively avoid getting electric shocks during his journey. The young chimp performed exceptionally well—and under incredible adversity, as NASA explains:

Ham performed these tasks well, pushing the continuous avoidance lever about 50 times and receiving only two shocks for bad timing. On the discrete avoidance lever, his score was perfect. Reaction time on the blue-light lever averaged .82 second, compared with a preflight performance of .8 second. Ham had gone from a heavy acceleration g load on exit through six minutes of weightlessness and to another heavy g load on reentry hardly missing a trick. Onboard cameras filming Ham’s reaction to weightlessness also recorded a surprising amount of dust and debris floating around inside the capsule during its zenith.

The successful mission set the stage for Alan Shepard, who became the first U.S. citizen to reach space in 1961. Ham lived the rest of his life in zoos.

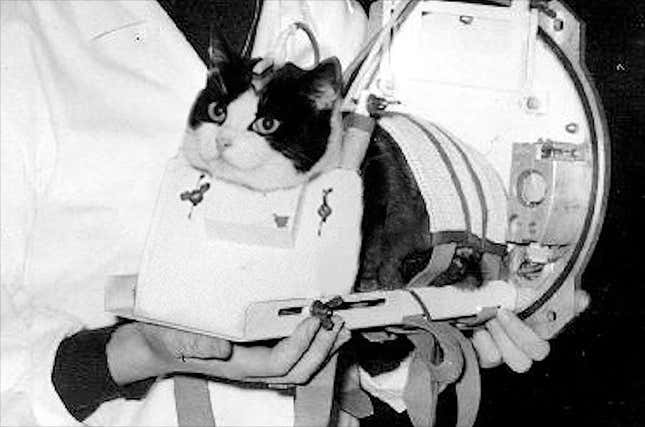

On October 18, 1963, the French space program launched Félicette—a stray Persian cat—into space. Electrodes were implanted into the cat’s skull to track neurological activity and to trigger physical responses. Either surprisingly or unsurprisingly (it’s hard to say which), Félicette remains the only cat to have been successfully delivered to space. Scientists euthanized Félicette shortly after the flight to study her brain.

In 2017, a crowdfunding campaign succeeded in building a memorial for Félicette—a bronze statue depicting the cat “perched atop Earth, gazing up toward the skies she once traveled.” The statue is currently located at the International Space University in France.

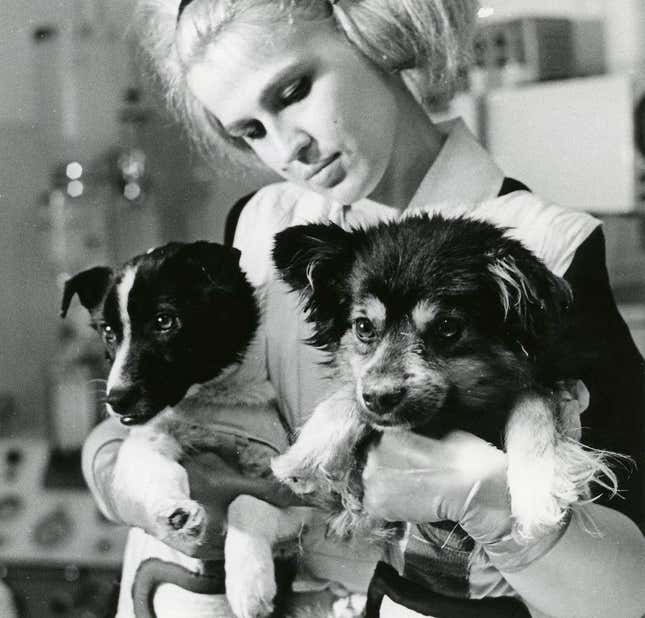

In February 1966, the Soviet space program launched the dogs Veterok and Ugolyok to beyond the protective Van Allen Belts, which they did to study the prolonged effects of space travel and the deleterious effects of radiation. The dogs stayed in space for 21 days, which remains the canine record. On their return, the dogs were dehydrated and they had lost weight. Veterok and Ugolyok also exhibited weakened circulation, muscle atrophy, and a loss of coordination; it took them an entire month to recover. Their restricted mobility likely had a lot to do with it, but it was an early sign that prolonged stays in space can produce bad health outcomes.

The 21 days in space remained a record for any animal—including humans—until the Soviet Soyuz 11 mission, in which three cosmonauts stayed aboard the Salyut 1 space station for 23 days. Tragically, the three men died during reentry and remain the only humans to have perished in space (the crew of the Space Shuttle Columbia was technically not in space when the shuttle disintegrated on February 1, 2003, resulting in their deaths).

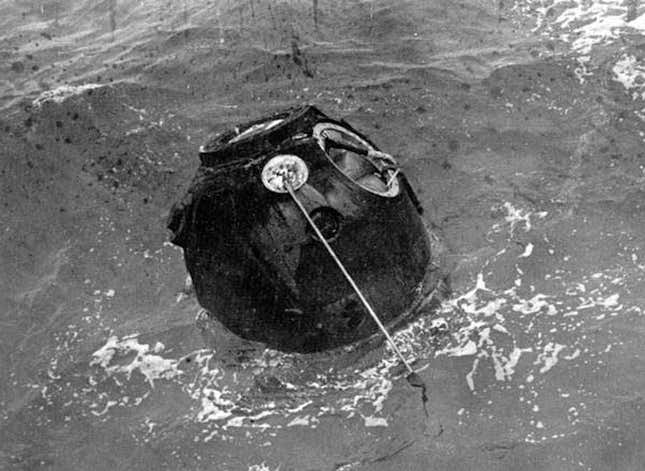

For the Soviet Zond 5 mission, a batch of living organisms took a historic trip around the Moon and back. Launched in 1968, the payload included a pair of Steppe turtles, hundreds of fruit fly eggs, worms, plants (including air-dried cells of carrots, tomatoes, peas, wheat, and barley), seeds, bacteria, and other creatures. No living creatures had ever ventured so far into space, and the mission ended successfully with the capsule splashing down in the Indian Ocean. The tortoises were still alive but at the point of starvation, the result of a 39-day fast. A duplicate mission later in the year suffered an anomaly that resulted in the loss of cabin pressure and the demise of all biological specimens.

A fish, specifically a mummichog (Fundulus heteorclitus), was sent to Skylab in 1973. Scientists were seeking to study the ways in which vestibular function, which controls balance in normal gravity, may be compromised in space. The tiny fish, along with a batch of fish that developed from embryos brought to space, exhibited strange swimming behavior, moving in loops. “The fish were probably responding to signals from extremely fine hairs in their otolith [a vestibular organ in fish] which straighten out in the absence of gravity,” according to NASA. “They reacted by swimming in a forward loop which was distorted into a sideways loop by the tendency to keep their backs to the light.” The fish, it would seem, were responding to light (i.e. visual cues) in the absence of gravity, which would normally allow them to discern up from down.

In 1973, scientists delivered Anita and Arabella, two common Cross spiders (Araneus diadematus), to Skylab 3. High school student Judith Miles wondered if microgravity conditions would prevent or somehow complicate the spiders’ ability to weave webs, and she proposed the Skylab experiment with scientists from the Marshall Space Flight Center. Both spiders struggled at first and were reluctant to do anything while in orbit, but with some prodding and access to rare filet mignon (yes, really) and water, the spiders began to weave rudimentary webs. Anita and Arabella got better at building their webs on subsequent attempts and their silky creations compared well to those made back on Earth. “Judy Miles’ experiment received a great deal of attention both within NASA and in the world press and indicated that there was keen interest in space experiments involving living organisms,” NASA described.

All seven crew members were killed during the 2003 Space Shuttle Columbia disaster, but something did pull through this awful episode: worms. Incredibly, containers of roundworms (C. elegans) managed to survive Columbia’s calamitous breakup. The nutrient solution in which they were stored served as a shield, as did the container. The worms also managed to reproduce and spawn a lineage that produced five generations in the months following the accident.

In one of the greatest feats of endurance, a batch of tardigrades managed to survive 10 days of exposure to open space. The experiment occurred in 2007 as part of the European Space Agency’s FOTON-M3 mission, and it established tardigrades, also known as water bears, as among the toughest organisms on the planet—and off. “Our principle finding is that the space vacuum, which entails extreme dehydration and cosmic radiation, were not a problem for water bears,” said TARDIS project leader Ingemar Jönsson, from the University of Kristianstad in Sweden.

As Space Shuttle Discovery prepared to launch for the STS-119 mission in March 2009, ground controllers noticed a bat clinging to the external fuel tank. Looking at images, wildlife experts believed the bat had broken a wing and was experiencing a problem with its right shoulder or wrist. Ground controllers hoped it would fly away on its own, but the bat stayed put, remaining visible on the fuel tank as the Shuttle cleared the tower. The ultimate fate of the bat was never determined, but it’s fair to say this story likely did not have a happy ending.