Halimi and Oubaali: Boxing champions united by different faiths

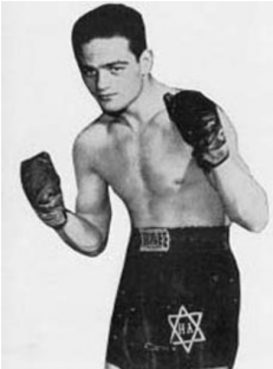

(RNS) — Both men are known for wearing their faith, if not on their sleeves, then on the biggest platforms they commanded in their respective time periods: For Alphonse Halimi, a French bantamweight boxer of the 1940s and ’50s, it was a Star of David stitched on his boxing trunks. His countryman and fellow bantamweight Nordine Oubaali, born more than half a century after Halimi, makes a bigger statement on Instagram, noting his celebration of Ramadan and other Muslim holidays.

Both men rode boxing from the edges of French society to international prominence: Halimi from the Jewish neighborhoods of Constantine, the third-largest city in the then-French territory of Algeria; Oubaali was born in Lens, in the cold and rainy Pas-de-Calais region in northernmost France, considered the boondocks in French popular culture.

It has been 61 years since Halimi lost his bantamweight crown in California — just as Oubaali did last month in a fourth-round knockout delivered by Nonito Donaire, a hugely popular Filipino American fighter and perhaps one of the top 50 fighters ever.

Halimi died in 2006. Together with Oubaali the duo forms a kind of time capsule of how sports function as an expression of faith solidarity and as a way to escape from lower-class struggle. The glamour of victory on the field or in the ring glosses over economic, religious and, above all, ethnic disparity to redeem lives that would otherwise be lived in shadows.

RELATED: New Topps cards focus on Muhammad Ali’s faith

Boxing has long drawn its contenders from tough, mostly urban environments. In the early half of the 20th century, several Jewish champions rose out of the ghettos where they were consigned. It was no less true for Algerian Jews than for their counterparts born to families from Russia or Poland.

An undated portrait of French boxer Alphonse Halimi. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

“Jews faced discrimination and antisemitism from settlers in Algeria and were not really accepted socially,” said Joshua Cole, an expert on French history at the University of Michigan. ”By the 20th century, Jews in Constantine had assimilated to French culture — they had adopted European dress and had access to French schooling if they wanted it, but they were looked upon as different from people of European descent.” In 1940, according to Cole, Halimi would have witnessed Jewish children being kicked out of public schools in Algeria by officials of the Vichy regime, which cooperated with France’s Nazi occupiers.

It was not unusual at the time for a French boxing champion to hail from North Africa. Marcel Cerdan, whom many consider the country’s greatest boxer ever (though perhaps best remembered for his extramarital romance with French singer Edith Piaf), was born to a pied-noir family in 1932. Halimi was known to carry a photo of Cerdan with him.

Nor were Jewish boxers an anomaly: Amateur boxing was one of the founding events at the Maccabiah Games, an international Jewish event founded the year Halimi was born. Halimi would headline the first international title fight to be held in Israel, just days before his own native land gained its independence in 1962.

Halimi was one of six Jews who held the world bantamweight crown from 1901, when Harry “The Human Hairpin” Harris won it, to 1957, when Halimi took the title. Four, including Harris, were American; in addition to Halimi, Robert Cohen, also from Eastern Algeria, won the weight class with a victory over a hometown fighter in Thailand in 1954, the year the Algerian war for independence began. Cohen’s victory inspired an Arabic language pop song that emphasized his Algerian, as opposed to his French, nationality.

The succession of Jewish fighters does not count former heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey, the most prominent fighter of the first half of the 20th century, who, though raised Mormon, was of partial Jewish ancestry.

The 21st century has seen its own super flyweight and bantamweight world champion of note, with Carolina Duer, an Argentinian, becoming the first person of Jewish ancestry to win a World Boxing Organization title from that country.

Given boxing’s history of lifting up minorities, it’s not surprising that a French Muslim would eventually rise to take their titles as Jewish boxers had. Due to discrimination and other factors, many French immigrants end up in “banlieues” — shorthand for the troubled communities outside French cities where unemployment and crime rates help to create a poverty trap.

“Xenophobia and racial discrimination are on the rise in France,” said Kamal Moummad, a French-Moroccan actor. “Sports and the world of boxing have therefore become the main platforms in which minorities can experience success, and accomplishments.”

Like Halimi, who had a dozen siblings, Oubaali comes from a large family — in his case, one with 18 children. His father, who died in 2000, encouraged his interest in boxing. “My parents came from Morocco in the 1960s to give us a better future,” Oubaali once told a French interviewer. “My father worked a lot: during the day in a Renault garage, at night at the (coal) mine and, during the holidays, he drove (buses) to go back and forth between France and Morocco.”

France’s Nordine Oubaali, right, sends a right to Japan’s Takuma Inoue in the sixth round of their WBC world bantamweight title match in Saitama, Japan, on Nov. 7, 2019. Oubaali defeated Inoue by a unanimous decision. (AP Photo/Toru Takahashi)

As an amateur, in his first trip to the United States, Oubaali took a bronze medal at the 2007 AIBA World Boxing Championships in Chicago. At the Olympics in 2008 and 2012 he faced controversial defeats but his 2012 campaign produced a bronze medal. In 2019, he won his World Boxing Council world title in Nevada, defeating Rau’shee Warren.

RELATED: NBA star Stephen Jackson on converting to Islam: ‘I needed to listen to my heart’

Oubaali is close friends with Hollywood actor Saïd Taghmaoui and with Souleymane Cissokho, another Olympic bronze medalist who provided French-language commentary ringside for Oubaali’s loss to Donaire. Taghmaoui’s breakout role was in the 1995 French film La Haine,” an ethnographic snapshot of life in the banlieues. Before that he was an amateur boxing star in France.

Few hubs are as important to the sport of boxing as Los Angeles. Both Halimi, in 1959, and Oubaali, in 2021, came to California seeking lucrative fights only to end up with knockout losses.

Halimi, for his part, would fight in the United States three times in his career, all in Los Angeles. He was a favorite of the Southern California boxing writers, and his Jewish faith was often noted in coverage of his fights.

Now deposed, Oubaali may take some inspiration from his Jewish predecessor. After losing the title in Los Angeles, Halimi was able to win the European bantamweight championship, a history that could show Oubaali a path to keeping his vow to bounce back from his defeat.