This Is Your Brain With a Migraine

New research seems to offer the closest look yet at how migraines might affect the brain. Scientists at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles collected detailed MRI scans from patients suffering from migraines. Compared to those without migraine, they found that these patients had a higher number of enlarged perivascular spaces, which may be a sign of damage to the small blood vessels of the brain. The findings could one day lead to new treatments for the chronic condition, the researchers say.

Migraines are a recurring type of headache that usually cause moderate to severe pain. Often, this pain is preceded or accompanied by other symptoms, such as nausea, fatigue, and a variety of sensory disturbances known as an aura, which can include seeing bright spots of light, ringing in the ears, or numbness and tingling along the body. These episodes typically last for hours, but they can sometimes persist for days to a week.

The exact cause of migraines is unclear, but there does appear to be a strong genetic component, since people with a family history of migraines are more likely to develop them. Migraines are thought to affect about 12% of the population, and women are more likely to report them than men. About 1% to 2% of the population is estimated to experience chronic migraines, or episodes that occur at least 15 days out of the month.

Migraines can be acutely managed with pain relievers, and some people have been able to lessen their frequency by avoiding known triggers, like certain foods. In recent years, the Food and Drug Administration has approved a new class of drugs that can more effectively treat or even prevent migraines. But there is still much we don’t understand about the condition, and there may be other avenues of treatment or prevention left to discover.

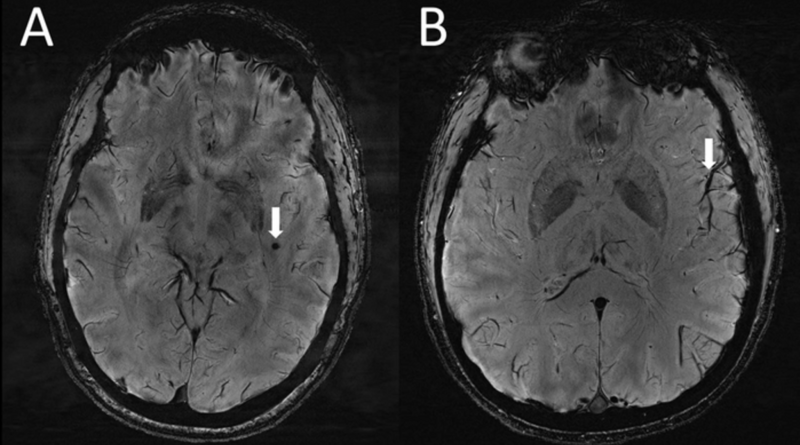

With their new research, USC scientists believe that they’re the first to look at the brains of migraine sufferers using a relatively novel form of ultra-high-resolution MRI known as 7T MRI. They scanned the brains of 20 people with migraines, 10 of whom had chronic migraines and 10 of whom had episodic migraines without aura. For comparison, they also looked at the brains of five healthy controls matched in age.

Across both migraine groups, the team found a greater number of enlarged perivascular spaces, which are fluid-filled pockets located near blood vessels in certain parts of the body, including the brain. These spaces were most prominent in the centrum semiovale, the brain’s central area of white matter. They also found that the presence of these spaces was linked to white matter lesions, though there wasn’t a significant difference in the severity of lesions found in people with or without migraines. The findings are set to be presented Wednesday at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

“Perivascular spaces are part of a fluid clearance system in the brain,” said Wilson Xu, an MD candidate at USC’s Keck School of Medicine, in a statement provided by the RNSA. “Studying how they contribute to migraine could help us better understand the complexities of how migraines occur.”

Enlarged perivascular spaces have been linked to other neurological ailments, such as dementia. But the team says it’s the first time that these kind of changes have been identified in this particular region of the brain in migraine sufferers. At the same time, they caution that the implications of what they found are uncertain.

While some studies in the past have suggested a connection between headaches and these enlarged spaces, for instance, others haven’t. It’s also not known why they might be appearing in sufferers. The scientists speculate that it could represent a breakdown in the brain’s glymphatic system, the system that uses perivascular channels to flush out waste products from the brain. Even if this hypothesis is true, it’s not clear whether these enlarged spaces are showing up as a result of migraines or if they’re playing a part in causing them. Lastly, the findings have yet to be formally peer-reviewed, which is an important part of the scientific process.

Still, this sort of basic research might be able to provide new leads toward migraine treatments and diagnostic tests, the researchers say.

“The results of our study could help inspire future, larger-scale studies to continue investigating how changes in the brain’s microscopic vessels and blood supply contribute to different migraine types,” Xu said. “Eventually, this could help us develop new, personalized ways to diagnose and treat migraine.”