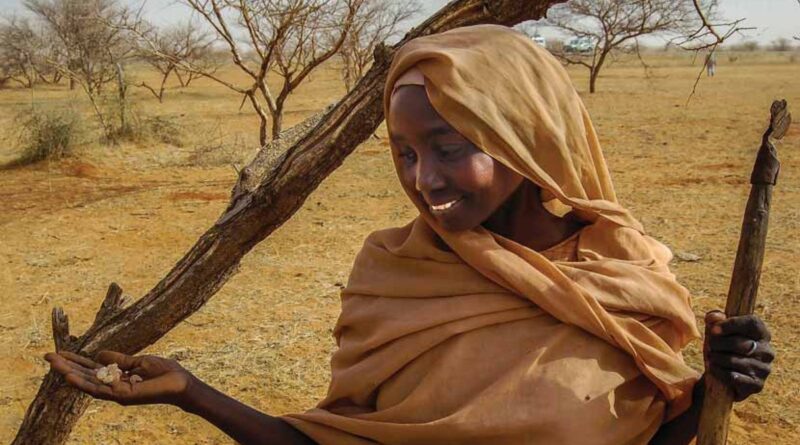

Sudan: As Sudan’s War Rages, Its Farmers Help Fill the Hunger Gap

A WFP-African Development Bank wheat project is boosting harvests amid catastrophic food insecurity

Standing in a field of golden wheat, Imad is a long way from his life as a mechanic in Sudan’s once-bustling capital of Khartoum. Today, the city lies in ruins after more than a year of civil war, and he has a new job working the land and harvesting its bounty in the northern village of Kubday.

“They gave us all we need and we farmed, thanks to God,” says Imad, 59 (whose last name is being withheld for his protection), referring to an emergency wheat production initiative financed by the African Development Bank and rolled out by the World Food Programme (WFP) in five Sudanese states.

As conflict rips this East African country apart, it seems unimaginable that Sudan can still deliver the harvests that long made it one of the largest agricultural producers in Africa and the Middle East. Yet, despite increased violence, many of the 170,000 smallholder famers enrolled in the wheat project are growing some of the food Sudan now desperately needs.

Indeed, in some the some of five states where the wheat initiative is taking place – Northern, Al Gezira, River Nile, White Nile and Kassala – some growers have boosted their wheat production by up to 70 percent this year. Those results offer a powerful lesson in how Sudan’s food security and its people could rebound, with the right support, if peace returned to the country.

“Not only did the project increase wheat production yields in the targeted states, but it also became a critical crisis-response intervention for internally displaced people,” says Mary Monyau, the African Development Bank Country Manager in Sudan, of the US$75 million initiative. “We expect continued positive outcomes from this project in the next season.”

The project is all the more important today, with the East African country producing just half its typical wheat harvest for a year. “The ongoing conflict in Sudan has had a devastating impact on agriculture,” says WFP Sudan Country Director Eddie Rowe. “Thanks to funding from the African Development Bank, we were able to mitigate some of the impacts of this war on wheat production.”

In some of the regions, like Northern State bordering Egypt – where Imad tills his land – nearly one-third of those participating in the project have been displaced by war.

“A huge number of farmers who are responsible for the wheat production in different states are the ones affected by war and needed support,” says Alrasheed Abdullah Fagiri, who heads the technical committee for the emergency wheat project. “Here in Northern State,” he adds, “we’ve seen excellent achievements.”

Under the project, farmers receive fertilizers and seeds. These are adapted to Sudan’s changing climate, which has ushered in increasingly more frequent and devastating droughts in recent decades. Desertification has swallowed up thousands of hectares of once-arable land. The inputs were game changers for smallholders – some of whom were eating seeds intended for planting, due to a lack of food. With the bank’s funding, WFP also introduced technologies and machinery such as combine harvesters, to save labour and money.

“It’s been a challenging farming season,” says Amira, agricultural manager in Al Dabbah town in Sudan’s Northern State. The WFP project has helped farmers in her region increase their harvests fivefold since it was launched three years ago. “The farmers received help until the harvesting stage,” she adds.

Other farmers are also reporting positive results. Together, they’ve produced nearly 645,000 metric tons of wheat this year alone – accounting for more than one-fifth of Sudan’s wheat needs.

Tackling the hunger crisis

Their yields are vital for a country that now hosts the world’s largest hunger and displacement crises. Of the nearly 26 million people battling severe hunger in Sudan today, 755,000 face catastrophic food insecurity – the most severe hunger category – according to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, a global standard for measuring food insecurity. Another 8.5 million people are experiencing emergency hunger conditions.

“This project is very important,” says WFP Sudan programme officer Karim Abdelmoneim, who was involved in the wheat project from its conception and hopes it will be extended beyond this year.

“It has become the only local source of wheat in a really devastating context,” Abdelmoneim adds. “People don’t have access to land to cultivate, because of the fighting.”

Feeding into these hunger numbers is the massive toll the war has taken on Sudan’s agriculture – the country’s most important economic sector, which accounted for one-third of its domestic income before the war. Fifteen months of fighting have displaced hundreds of thousands of farmers. Yields of staple cereals are more than 40 percent below their normal five-year average, the UN Food and Agricultural Organization reports.

Sign up for free AllAfrica Newsletters

Get the latest in African news delivered straight to your inbox

Once-productive fields in places like Gezira State – the country’s breadbasket, where half Sudan’s wheat and 10 percent of its sorghum is usually grown – have transformed into battlefields. But farming is still viable in more stable areas like Northern State, where many conflict-displaced people have settled.

“This assistance came at a time when we were in need,” says farmer Imad of the emergency wheat project.

After fleeing the fighting in Khartoum with his family last year, Imad sought shelter in Kubday, his native village. “The people welcomed us, and give us land in the Kubday agricultural project,” he says of the emergency wheat initiative which has enrolled other war-displaced people.

“Host families shared their unused farmlands with the newcomers,” says Fagiri, the technical committee expert. “We expected only 10 percent of farmers would grow wheat,” he adds, “but the project was able to grow that to 40 percent.”

Imad ticks off other improvements he would like to see: solar power for irrigation, and better prices for his crops. He also lays out longer-term goals for his family, for when Sudan’s war ends.

“We might settle here,” he says, “because we’ve found out agriculture is good business.”