When Risks Become Reality: Extreme Weather In 2024

When Risks Become Reality: Extreme Weather in 2024 is our annual report, published this year for the first time.

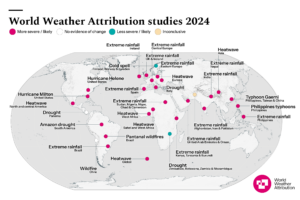

Every December, people ask us how severe the year’s extreme weather events were. To answer this question, we’ve partnered with Climate Central to produce a report that reviews some of the most significant events and highlights findings from our attribution studies. It also includes new analysis looking at the number of dangerous heat days added by climate change in 2024 and global resolutions for 2025 to work toward a safer, more sustainable world.

Key messages

- Extreme weather reached dangerous new heights in 2024. This year’s record-breaking temperatures fueled unrelenting heatwaves, drought, wildfire, storms and floods that killed thousands of people and forced millions from their homes. This exceptional year of extreme weather shows how dangerous life has already become with 1.3°C of human-induced warming, and highlights the urgency of moving away from planet-heating fossil fuels as quickly as possible.

- Climate change contributed to the deaths of at least 3,700 people and the displacement of millions in 26 weather events we studied in 2024. These were just a small fraction of the 219 events that met our trigger criteria, used to identify the most impactful weather events. It’s likely the total number of people killed in extreme weather events intensified by climate change this year is in the tens, or hundreds of thousands.

- Globally, climate change added on average 41 additional days of dangerous heat in 2024 that threatened people’s health, according to new analysis by Climate Central. The countries that experienced the highest number of dangerous heat days are overwhelmingly small island and developing states, who are highly vulnerable and considered to be on the frontlines of climate change. The analysis highlights the wide reaching impacts of extreme heat that are underreported and not well understood.

- Many extreme events that took place in the beginning of 2024 were influenced by El Niño. However, most of our studies found that climate change played a bigger role than El Niño in fueling these events, including the historic drought in the Amazon. This is consistent with the fact that, as the planet warms, the influence of climate change increasingly overrides other natural phenomena affecting the weather.

- Record-breaking global temperatures in 2024 translated to record-breaking downpours. From Kathmandu, to Dubai, to Rio Grande do Sul, to the Southern Appalachians, the last 12 months have been marked by a large number of devastating floods. Of the 16 floods we studied, 15 were driven by climate change-amplified rainfall. The result reflects the basic physics of climate change — a warmer atmosphere tends to hold more moisture, leading to heavier downpours. Shortfalls in early warning and evacuation plans likely contributed to huge death tolls, while floods in Sudan and Brazil highlighted the importance of maintaining and upgrading flood defences.

- The Amazon rainforest and Pantanal Wetland were hit hard by climate change in 2024, with severe droughts and wildfires leading to huge biodiversity loss. The Amazon is the world’s most important land-based carbon sink, making it crucial for the stability of the global climate. Ending deforestation will protect both ecosystems from drought and wildfire, as dense vegetation is able to absorb and retain moisture.

- Hot seas and warmer air fueled more destructive storms, including Hurricane Helene and Typhoon Gaemi. Individual attribution studies have shown how these storms have stronger winds and are dropping more rain. Research by Climate Central found that climate change increased the intensity of most Atlantic hurricanes between 2019 and 2023 – of the 38 hurricanes analysed, 30 had wind speeds that were one category higher on the Saffir-Simpson scale than they would have been without human-caused warming, while our analysis found that the risk of multiple Category 3-5 typhoons hitting the Philippines in a given year is increasing as the climate warms.

Resolutions for 2025

- A faster shift away from fossil fuels – The burning of oil, gas and coal are the cause of warming and the primary reason extreme weather is becoming more severe. Last year at COP28, the world finally agreed to ‘transition away from fossil fuels,’ but new oil and gas fields continue to be opened around the world, despite warnings that doing so will result in a long term commitment to more than 1.5°C and therefore costs to people around the world. Extremes will continue to worsen with every fraction of a degree of fossil fuel warming. A rapid move to renewable energy will help make the world a safer, healthier, wealthier and more stable place.

- Improvements in early warning – Weather disasters in 2024 highlighted the importance of early warning systems, which are one of the cheapest and most effective ways to minimise fatalities. Warnings need to be targeted, given days ahead of a dangerous weather event, and outline clear instructions on what people need to do. Most extreme weather is well forecast, even in developing nations. Every country needs to implement, test and continually improve early warning systems to ensure people are not in harm’s way.

- Real-time reporting of heat deaths – Heatwaves are the deadliest type of extreme weather. However, the dangers of high temperatures are underappreciated and underreported. In April, a hospital in Mali reported a surge in excess deaths as temperatures climbed to nearly 50°C. Reported by local media, the announcement was a rare example of health professionals raising the alarm about the dangers of extreme heat in real-time. Health systems worldwide are stretched, but informing local journalists when emergency departments are overwhelmed is a simple way to alert the public that extreme heat can be deadly.

- Finance for developing countries – COP29 recently discussed ways to increase finance for poor countries to help them cope with the impacts of extreme weather. Developing countries are responsible for a small amount of historic carbon emissions, but as our research has highlighted this year, are being hit the hardest by extreme weather. Back-to-back disasters, like the Philippines typhoons, or devastating floods that followed a multi-year drought in East Africa, are cancelling out developmental gains and forcing governments to reach deeper and deeper into their pockets to respond and recover from extreme weather. Ensuring developing countries have the means to invest in adaptation will protect lives and livelihoods, and create a stabler and more equitable world.