Africa: Late Diagnosis Is Turning Cancer Into Death Sentence in Africa

African women die of breast cancer within five years in four out of five cases, compared to early diagnosis in developed countries.

A growing number of cases of cancer and high mortality rates make cancer one of the most significant health issues in Africa. It is estimated that 50% of cancer cases in Africa involve breast, cervical, prostate, colorectal, and liver cancers in adults. If urgent measures are not taken, cancer mortality in the region will reach approximately one million deaths by 2030, a pressing public health issue.

World Economic Forum reports that breast and cervical cancer account for nearly a third of all cancer-related deaths among women in sub-Saharan Africa. Cancers like cervical and breast cancer are treatable when caught early – but global health disparities are making early detection, diagnosis, and treatment difficult. Cancer in childhood remains a devastating challenge worldwide and in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), survival rates are often below 30%, and sometimes even below 10%.

“Cancer is an important health issue in Africa,” said Project ECHO Africa’s Director, Dr. Caroline Kisia. “But there are significant disparities, particularly when it comes to access for rural or remote areas.”

She said that late diagnosis is one major issue in Africa. “Cancer tends to be diagnosed late, and when it has already metastasized, treatment becomes difficult, harsh on the patient, and the prognosis tends to be poor,” she said.

“Four out of five women in Africa diagnosed with breast cancer will die within five years,” said Dr. Kisia. “Yet, when you go to the more developed Western countries, breast cancer diagnosis is not a death sentence. Most of their patients will survive.”

“The difference is that their patients’ diagnosis is made early and because diagnosis is made early, there’s a much higher chance of effectiveness when it comes to treatment,” she said. “It is expected that the number of new cancer cases within sub-Saharan Africa will continue to rise.”

But what is Project ECHO?

Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) began in 2003 at the University of New Mexico founded by Dr. Sanjeev Arora, a gastroenterologist. Dr. Arora treated Hepatitis C patients but faced an overwhelming eight-month waiting list at the state’s largest referral hospital, resulting in many patients, especially those from rural areas, not receiving timely treatment.

Dr. Arora began the project after a 43-year-old woman with Hepatitis C failed to seek treatment for years due to the logistical challenges of traveling and her responsibilities as a mother. By the time she saw Dr. Arora, her condition had progressed to liver cancer, and she died six months after beginning treatment with him. This tragic outcome motivated Dr. Arora to provide guidelines for treating Hepatitis C to local healthcare providers. As a result, they can treat patients within their communities, removing barriers to care and laying the foundation for Project ECHO.

There are 290 active programs in 30 African countries, 230,000 unique participants, and over 900,000 ECHO sessions across the continent. A unique participant is an individual healthcare worker logged into an ECHO session from anywhere in Africa.

A total of 54 countries in Africa participate in ECHO sessions

“Our footprint is quite significant across the African continent,” said Dr. Kisia. “This is important because African countries have been working hard to increase digitization across their countries, to increase internet access across the countries. So, what ECHO is doing is leveraging on that infrastructure to make sure that this content flowing through that infrastructure where healthcare workers can get the information that they need from a trusted human network.”

Bridging the Healthcare Gap

Dr. Kisia said that they had conversations with 19 ministries of health in Africa about their top priorities, and when it came to top priorities, they had various categories of diseases. The first was infectious diseases, where you discussed HIV, TB, malaria, diarrheal diseases, and antimicrobial resistance. In the second category, she said, we’re talking about non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, mental health issues, and cancer. The other significant issues are maternal and child health, nutrition, and food security. Cancer has a significant impact on mortality and morbidity in Africa.

“It has been identified as an important issue by African ministries of health,” she said. “So from a Project ECHO perspective, it becomes one of the priority issues we want to deal with.”

“African nations face significant challenges when it comes to health workforce numbers, particularly when it comes to specialists, who are largely concentrated in cities,” she said. “The access to accurate early cancer diagnosis, so that someone can be referred for the necessary treatment, becomes a bit problematic in rural areas.”

“We talk about moving knowledge instead of moving people.”

Dr. Kisia said that the challenge Africa is confronting is a severe shortage of healthcare workers.

“The sub-Saharan African region, with approximately 15% of the world’s population, carries the burden of 24% of the world’s diseases,” she said. “Yet, we are only home to 3% of the global healthcare workforce.”

“What Project ECHO does is leverage technology to connect these experts in urban areas with the rural healthcare workers, where the vast majority of African communities live,” said Dr. Kisia. “Then we use video conferencing to hold regular meetings between experts and frontline healthcare workers to discuss specific cases that the frontline healthcare workers are facing.”

“As a result,” she said, “the experts can contribute to the thinking and the management of patients that frontline healthcare workers are handling in rural and remote areas.”

“Therefore, we talk about moving knowledge instead of moving people,” Dr. Kisia said. “So instead of patients having to come to the urban areas, if a healthcare worker close to them with the support of an expert and utilizing technology to facilitate that conversation regularly, with all the necessary information, it becomes possible for that healthcare worker to see the patient and assist them closer to where they are.”

AI-Enabled Telemedicine

Telemedicine offers a transformative opportunity to improve access to early cancer diagnosis and screening, especially in remote areas, through the incorporation of artificial intelligence and mobile technology. Dr. Kisia said that the transformative role of mobile technology and telemedicine in improving access to early cancer diagnosis, particularly in remote areas.

“Technology has advanced, which is good,” she said. “The fact that Project ECHO is accessible via any internet-connected computer or mobile phone is very important to us, and mobile technology has greatly transformed the way Project ECHO human networks can be accessed.”

“A lot of healthcare workers in Africa, especially in low-income countries, participate in Project Echo sessions from their mobile phones, she said.

“The Project ECHO app is installed on my mobile phone. I joke with people that I can attend a Project ECHO session seated in my grandmother’s house in the village,” Dr. Kisia said. “As long as I have a signal on my phone and can make or receive a telephone call, and I have access to the Internet on my smartphone and I have data bundles on my phone, I can join an Echo session from anywhere.”

“Many of our healthcare workers are located in rural facilities, so mobile phones have made it easier for patients to be able to access Project ECHO sessions and to access information in general,” she said.

Regarding cancer diagnosis, Dr. Kisia said mobile technology impacts specific screening methods.

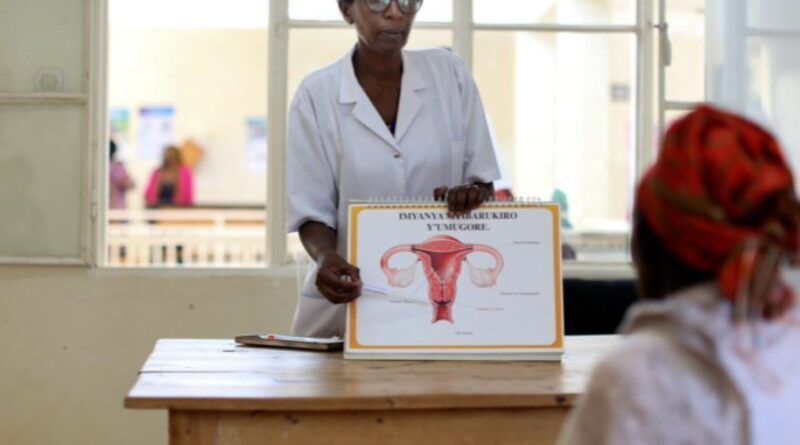

“As far as cancer is concerned, mobile technology has provided highly complementary advancements”, she said. “There are some screening methods, such as the use of damascopes to examine the skin and visual inspections of the cervix for cervical cancer, that can be conducted with inexpensive equipment and a mobile device. By combining these innovations with human networks, such as Project ECHO, we can significantly reduce the number of late or missed diagnoses of cervical cancer by encouraging people to go for screenings, and by providing a greater amount of information and support to healthcare providers.”

“Technology is making a significant difference,” she said.

However, Dr. Kisia said that one of the main challenges in implementing Project ECHO is Internet access.

“A key challenge is actually access to the internet. If you’re in a place where there’s no access, it means that healthcare workers cannot benefit from the health information available through networks like ECHO or other similar platforms.”

Project ECHO Combats Childhood Cancer in Kenya

Children in western Kenya, where malaria is also prevalent, are particularly susceptible to Burkitt lymphoma, as most childhood cancers go undiagnosed and untreated until it is too late. Childhood cancers of the blood, eyes, and kidneys are also prevalent in Kenya. Project ECHO and Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) launched the AMPATH oncology ECHO platform in January 2020 in response to poor outcomes in childhood cancer care at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) and throughout western Kenya. It covers 15 counties now.

“In 2010, Western Kenya’s largest teaching and referral hospital identified that only about 6% of the expected childhood cancer cases were being diagnosed,” said Dr Kisia. “The projections of the prevalence of cancer in the region should have led to over 1,500 children being diagnosed with cancer, but in reality they are only diagnosing about 100, meaning they are really only diagnosing a small percentage.”

AMPATH Kenya, launched the Pediatric Oncology ECHO in 2020, and within a year, counties with high participation in ECHO sessions diagnosed 17 more children than counties with low participation. In 2021, there was a 17% to 18% increase in expected pediatric cancer cases, which was an increase of 11% to 12% since 2010.

“When you have timely and accurate diagnosis, children can begin treatment earlier, preventing avoidable treatment failures or deaths that occur when diagnoses are delayed,” she said.

The goal of ECHO, according to Dr Kisia, is to empower these healthcare providers.

“The healthcare providers who are in smaller facilities that do referrals to the main teaching and referral hospital in Western Kenya are being empowered with expertise and supported so that they can make these complex diagnoses and refer patients earlier to get treatment early,” she said. “The same is true for other types of cancer, such as gynecological cancers, breast cancers, and lung cancers, where timing of diagnosis is so important.

“Our main goal at ECHO is to ensure we can extend our interventions to more places in Africa, around the world, that will help to promote early detection of cancer,” said Dr. Kisia. “As an example, with cervical cancer, we have ECHOs that encourage early detection, raise community awareness, encourage early screening, encourage people to get screened, work with healthcare workers to recognize suspicious signs of cervical cancer, and then refer them to the appropriate place for appropriate treatment.”

“We believe that early detection of cancer is important, whether it be cervical cancer or breast cancer or childhood cancer or other types of cancer because it allows for early intervention, which can be lifesaving for the affected individuals,” she said.

Early Cancer Detection Saves Lives

Dr. Kisia has said that Project ECHO has increased access to cancer care in rural areas by enhancing the knowledge and awareness of frontline healthcare workers.

“What happens is that by connecting frontline healthcare workers with experts through ECHO, we educate them on the signs they should be looking out for. It is like the example we discussed in Western Kenya regarding childhood cancers, where many children were treated, would appear before a medical officer and would be treated for a wide range of conditions before anyone thought, “Might this be cancer?” she said.

“By educating healthcare workers, you can increase their index of suspicion so that if they are faced with a patient who presents with a certain set of symptoms, they must ask themselves, might this be cancer?… As a result, having that awareness, and having that increased index of suspicion increases the chances that the healthcare worker will do the necessary tests to find out if this might be cancer.”

“Therefore, ECHO works to increase awareness, by helping to educate the frontline healthcare workers, so that they can have a higher index of suspicion and investigate patients appropriately so that possible cancer cases can be identified early enough so that interventions can be made,” she said.

Overcoming Barriers to NCD Prevention in Developing Nations

According to Dr. Kisia, Project ECHO is key in addressing both communicable and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) throughout Africa and India.

“Project ECHO has been used to treat various communicable and non-communicable diseases,” she said. “So for example, right now we are talking about cancer. In Africa, we are currently experiencing a double pandemic when it comes to things like diabetes, hypertension, or mental health issues.”

“We already have a pandemic of infectious diseases, whether it’s HIV, malaria, TB, and so on. In addition, we’re dealing with a pandemic of non-communicable diseases. We witnessed mental health issues being brought to the forefront during COVID-19.”

She stressed the importance of early diagnosis, especially for NCDs, and shared an example from Kenya, where the government works closely with community health workers. “Currently, diabetes, hypertension, and cancer are on the rise significantly on the continent. As we discussed a bit about cancer, one of the most important things when it comes to other NCDs like diabetes and hypertension is early diagnosis. So how do we achieve early diagnosis? The first step to achieving early detection is to make people aware of what to look for,” she said.

“The first step to achieving early detection is to make people aware of what to look for.”

“Right now, in my country, Kenya, we have a strategy for working with community health workers,” said Dr. Kisia. “The Kenyan government has developed a strategy to work with community health workers. The aim is to ensure that community health workers who live in the community, who see various households on a regular basis, know the signs and symptoms to look out for in the communities.”

“They go to a particular household and hear someone say, “I’m not feeling well.” I’ve been suffering from a headache that won’t go away. All I have is this, that, the other, and the other.

If someone complains of persistent headaches or unusual symptoms, they are taught to ask critical questions, like, ‘When was the last time your blood pressure was checked?’ or ‘Have you had your blood sugar tested?'”

Dr. Kisia also said that there have been technological advances, like small blood sugar testing devices, that are empowering community health workers to perform quick tests.

“A community health worker can do a blood sugar test right there in the household and advise the person to visit the nearest health center if needed,” she said. “Once at the health center, the healthcare workers – who’ve been trained through ECHO to have a high index of suspicion – can further assess and diagnose conditions like diabetes or hypertension.”

“So basically, we are saying that even for non-communicable diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes, screening will improve patient identification earlier,” said Dr. Kisia. “We know that when patients are started on treatment and if the healthcare workers have sufficient knowledge to ensure that we have good control of blood pressure, good control of blood sugar, we can prevent more complicated things like the kidney disease that comes or the heart disease that comes. In addition to kidney disease and kidney damage caused by diabetes, heart disease, and hardening of the blood vessels caused by hypertension and high blood pressure, we also experience kidney disease.”

She said “If we control blood sugar levels well, we can avoid more complicated and expensive treatments like dialysis or kidney transplants. This is critical because the resources for healthcare in African countries are limited and by preventing these severe outcomes, we ensure that our healthcare systems can provide more care to a larger population.”

A Call to Action

Dr. Kisia shared some stories that are close to her heart.

“As a mother, I can only imagine the pain a parent goes through when their child keeps getting sicker, and yet the diagnosis comes too late,” she said. She said that the impact of Project ECHO is helping to increase timely diagnoses, which allows children to receive treatment early and ultimately survive. “Being able to save lives by diagnosing children in time so they can grow into adulthood is something very close to my heart.”

One other thing that’s close to my heart is when we talk about things like breast cancer and cervical cancer. “There is no reason why for us a breast cancer diagnosis or a cervical cancer diagnosis should be a death sentence. When for somebody like us living in one of the other western developed countries, a diagnosis like that will be done early enough and they’re able to get treatment early enough and they continue with their life.”

Dr. Kisia said we need to take action as cancer prevention and timely diagnosis are vital for saving lives. “It’s our relatives – our uncles, aunts, grandmothers, mothers, sisters, and children – are dying of cancer when it can be prevented,” she said. “The importance of ongoing support, knowledge sharing, and virtual mentoring of frontline healthcare workers in low-resource settings to prevent cancers like cervical cancer, which can be avoided through HPV vaccination or cured if caught early.”

“Through culturally sensitive conversations tailored to communities’ beliefs, we can promote both primary prevention, like tobacco cessation to prevent lung cancer, and secondary prevention, where cancers such as cervical cancer can be caught early and treated before it’s too late.”

Future plans

As Dr. Kisia pointed out, Project ECHO now has a presence in 30 African countries and plans to expand the program to other low- and middle-income countries.

“ECHO began working in Africa in Namibia in 2015, initially focusing on HIV and AIDS. It has since spread to many other countries, including Zambia, where it is used to treat HIV, AIDS, and tuberculosis (TB). ECHO also played a key role in responding to public health challenges around the world during the COVID-19 pandemic,” she said.

Sign up for free AllAfrica Newsletters

Get the latest in African news delivered straight to your inbox

“Actually, during COVID, that’s when the use of ECHO across the continent grew. Because at that time, it was a new illness, healthcare workers needed to get access to information to be able to manage patients effectively,” she said. “So as we speak, we want to make sure that we can continue growing ECHO across the continent.”

Dr. Kisia said that the University of New Mexico recently established ECHO Africa, headquartered in Nairobi, and she was appointed as its director. Her role focuses on expanding Project ECHO across all African countries and deepening its use in regions where it’s already active. “There are many different illnesses that can benefit from the use of ECHO,” she said.

“We want to make sure that we are expanding across the continent, but also in countries that are already using ECHO, that we can continue to strengthen the use of ECHO to serve more and more and more communities. In order to be able to do that, we partner with others. For ECHO, partnership, and collaboration are key because it’s only through partnerships that we’ll be able to get the sort of impact that we’d like to see across the continent.”

“As we speak, we have partnerships with 20 African ministries of health with which we have signed partnership agreements and with which we are working to get ECHO implemented in their countries. We also partner with other non-profits, private sector, academic institutions, and NGOs,” she said.

Dr. Kisia said that due to the outbreak of Mpox in multiple countries across Africa, they’re also working with the Africa CDC.

“We’re using the ECHO platform to increase access to information on Mpox, covering prevention, patient care, and protocols for handling diagnosed cases to slow the spread in communities,” she said. “The plan in Africa is to continue to grow the ECHO network across the continent to make sure that our communities are benefiting from increased access to healthcare.”

Dr. Kisia said that there is a huge shortage of healthcare workers, and so what Project ECHO does is enable healthcare workers to provide higher quality care, but also shift work onto the ECHO platform, enabling task shifting. Through this approach, non-specialist medical officers can gain the skills and knowledge needed to treat patients effectively in their communities, just as Dr. Arora did by training others to handle cases that require a specialist.

She proposed the concept of “force multiplication” within the healthcare workforce. “By equipping non-specialist providers with specialty expertise, we can achieve force multiplication, allowing healthcare workers who would otherwise not treat certain cases to do so effectively,” she said.

“Before ECHO was used in Namibia for HIV and AIDS, HIV treatment was considered quite complicated. By using ECHO, the specialists could attend, to deal with the doctors that see these patients where they are, instead of them having to travel from the peripheries to the capital,” said Dr. Kisia. “We discuss patient cases and help advise their doctors on how to manage those patients. This means that the necessary medications can be sent to peripheral clinics, allowing patients to receive treatment closer to home.”

“We want to ensure that we continue to empower more healthcare workers and support task shifting, enabling more patients to receive treatment in their communities,” she said.

We have to get innovative

As a continent, we have significant healthcare challenges, said Dr. Kisia.

“We carry 24% of the global disease burden while having only 3% of the global healthcare workforce. In Sub-Saharan Africa, only 1% of the money spent on healthcare worldwide is spent on the 24% disease burden, which means that we have a challenge,” she said. “And when we have a challenge, we have to think outside the box.”

“We have to get innovative. We have to say, how can we support the limited healthcare workforce that we have to be able to do their job better? The ECHO platform and Project ECHO are examples of how we can do this so that our healthcare workers have access to actionable information. We can address real-world challenges they face through case-based learning.”

Through virtual mentoring, we are leveraging technology to ongoing mental healthcare workers. We can support them to increase the quality of care that patients and communities on the African continent are getting so that we increase the efficiency in our healthcare system, we increase the quality of care that patients are getting, and we increase access to healthcare for our African communities. That way, even with our limited resources, we can make sure we are getting the greatest value that we can get when it comes to healthcare for our communities,” she said.