How Walter Payton, Buddy Ryan and the ’85 Bears helped shape Ron Rivera’s coaching career

12:10 PM ET

-

John KeimESPN Staff Writer

Close

- Covered the Redskins for the Washington Examiner and other media outlets since 1994

- Authored or co-authored three books on the Redskins and one on the Cleveland Browns

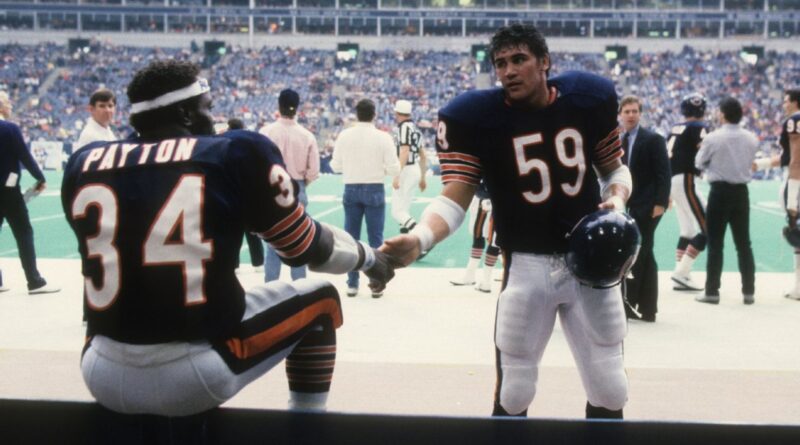

ASHBURN, Va. — Ron Rivera was chatting with former Chicago Bears teammate Walter Payton on the sidelines during a game in 1996. The conversation started about a defensive call; it ended with Rivera traveling a new career path, with Payton clearing the way.

Payton was on the Bears’ board of directors, and also doing some TV work; Rivera was working for a local TV station.

“He’s the one that got me my [coaching] job,” Rivera said.

The Bears selected Rivera in the second round of the 1984 draft out of Cal, and he played nine seasons in Chicago, including the most celebrated in franchise history. The 1985 team remains the Bears’ only Super Bowl champion, and even though Rivera wasn’t a key player on perhaps Chicago’s most beloved team, he’ll still be viewed through that prism when he leads the Washington Commanders into Soldier Field for Thursday night’s game (8:15 p.m. ET, Prime Video).

Rivera played with a number of memorable characters, some of whom helped shape his coaching style — like former defensive coordinator Buddy Ryan.

But Payton was the one who helped turn him into a coach. During that season opener vs. Dallas, the two were standing behind the Dallas bench when they heard a coach tell the linebackers to force a run toward the corner. Rivera told Payton he’d force it back inside because, “That corner doesn’t want to tackle anybody.” Rivera predicted the next time Chicago ran that play it would gain 10 to 12 yards.

He was right. The corner handled it the way Rivera anticipated. And Payton turned to him and said, “Why aren’t you coaching?”

“I said, ‘Walter, I don’t know how to get in.’ He said, ‘I’ll tell you what. You come see me tomorrow in my office,'” Rivera remembered.

Payton set up a meeting between Rivera and Bears chairman Ed McCaskey. After the season, Rivera talked to then-head coach Dave Wannstedt, who hired Rivera as a defensive quality control coach.

“The rest is history,” said Rivera, a two-time NFL Coach of the Year.

In Rivera’s office at the Commanders’ facility, he has a Lombardi Trophy replica from the 1985 season — a gift from the Bears commemorating the 25th anniversary of that team. Also, Washington’s senior director of player development Malcolm Blacken painted him a picture of a blue tattered Walter Payton jersey that is framed in his office. Payton died of a rare liver disease and bile duct cancer in November 1999.

Rivera’s memories include a unique group of people and talent: coach Mike Ditka, Ryan, quarterback Jim McMahon and defensive tackle William “The Refrigerator” Perry, among many others.

“It’s part of me,” Rivera said of the ’85 Bears. “We were a cast of characters.”

As former teammate Jim Morrissey said, they had heavy people rooting for the 325-pound Perry, wrestling fans clamoring for defensive tackle Steve “Mongo” McMichael, and then there was McMahon.

“He was crazy all day, every day,” Morrissey said. “He affected the defense as much as the offense. It was a crazy group of guys intent on winning.”

And the memories remain strong nearly 40 years later.

‘He told me where to go, and the ball ended up where he told me to go’

While Rivera might not have been one of the main personalities, he did have an influence. He was known as someone who loved studying and analyzing the game.

“Ron was the type of guy to spend hours watching that tape, because he was required to be perfect in his job with Buddy,” said former Bears offensive lineman Tom Thayer, currently a color commentator for the Bears’ radio crew. “He didn’t have a chance to make multiple mistakes. I could see his immediate recognition of the offensive clues.”

And because he backed up all three starting linebackers, Rivera had to know each position. In 1986, he earned Player of the Week honors filling in for injured starting middle linebacker Mike Singletary.

“I remember [Dan] Hampton and McMichael giving Singletary a hard time, ‘You better get healthy,'” Morrissey said.

Morrissey felt Rivera’s impact most during Super Bowl XX. Near the end of their 46-10 win over New England, Morrissey — a linebacker who was more of a special team standout — was inserted into the game. Ryan had never let him practice with the defense, because as Morrissey said, “He didn’t think I had earned that right.”

Morrissey had no idea how to handle a particular look if it turned into a pass. After breaking the huddle, he asked Rivera, who told him to drop back to his left in that situation. So Morrissey did — and promptly intercepted a pass, returning it 47 yards to the 4-yard line.

“He told me where to go, and the ball ended up where he told me to go,” Morrissey said.

‘He always stood up for us’

To the outside world, McMahon was the “punky QB” who wore headbands, spiked hair and challenged authority. To Rivera, he was a guy who took care of his teammates. One training camp, Rivera thought it was before the ’85 season, the Bears had what he considered a brutal morning practice: full pads and physical.

As they warmed up for the second practice of the day, Rivera heard McMahon shouting to Ditka. “Hey, Iron [Mike]. Hey, why don’t you ease up on the boys? It was a pretty rough day this morning. Man, what’s wrong with you? Come on.”

To this day, Rivera said, he thinks it might have been a setup, but it didn’t matter. After all, the players benefitted.

“He just kind of got on him, and Ditka goes, ‘Well, what do you want me to do about it?'” Rivera said, “He says, ‘Why don’t you give the guys the afternoon off?’ He said, ‘Really? All right.’ He blew a whistle, ‘Take it in. We’re done.’ It’s like everybody got fired up.

“So from that point, I always felt he always stood up for us, Jimmy Mac did. Always stood up for us.”

Another time, McMahon started riding a moped around training camp at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville campus, where the Bears held training camp. That led to him buying his offensive linemen red scooters. And that led to their new nickname: the Red Riders.

“He used to do all those things,” Rivera said. “One year, it might have been the Super Bowl year, he paid this bar owner the last night just before camp was to break a little extra to close it down to just the players and select friends.”

‘It’s always about setting the standard’

Ditka was among the bigger personalities, made even more famous by skits on “Saturday Night Live.” But for Rivera, what he remembers is Ditka’s philosophy.

“The biggest thing I learned about Mike, really, is you have to set the standard,” Rivera said.

Rivera remembered one training camp workout in the late 1980s when the Bears were having, as he called it, a brutal day. It was hot. Ditka was “motherf—ing us the whole time and wouldn’t stop.” After practice, Rivera, also a players’ representative at the time, met with Ditka about a matter.

Then he asked the coach a question: Why was he on them so hard that day?

“He said, ‘Ronnie, I would never ask you to do something I couldn’t do,'” Rivera said. “I go, ‘Huh.’

“Then the realization hit me. He was a Hall of Famer, so his standard is actually pretty doggone high. So he was pushing us. So to me, it’s always about setting the standard and making sure it’s a high standard so you can push into it.”

Rivera also recalled how Ditka handled Super Bowl week in New Orleans. Rivera said the Bears arrived a day earlier than they needed to, and Ditka threw them a party. Then, he announced, there was no curfew until the Friday and Saturday before the game.

“We had a good time, and we enjoyed it,” Rivera said. “I think that’s what made us so unique, the personalities, the characters. The head coach was a personality, and they were all out there. The defensive coordinator was a personality.”

‘He was a tremendous, tremendous motivator and coach’

Tension existed between Ditka and Ryan, whether in practice or games. Thayer recalled having intense practice sessions stemming from their competitiveness — Ditka on the offensive side; Ryan on defense. In nine-on-seven run drills, Thayer said Ditka would yell at Ryan about being in a particular look. Ryan would yell at his guys that they weren’t playing hard enough.

“He didn’t care who was carrying the ball, he wanted them to give him a hit,” Thayer said.

Rivera said he’d hear the two bicker during games about how to handle a certain tactic by the opponent. One time Rivera said he heard Ditka yell at Ryan, “Hey! I’m the head coach, and until I’m not the head coach, we’ll do things my way.”

Ryan was perceived as a big personality. His players loved him and didn’t consider him a bombastic coach. He was a combat veteran, having served during the Korean War, and assumed a leadership role when his sergeant was killed. His wife relayed that information to the players, because, Rivera said, Ryan never talked about it.

But Ryan transferred some of the mentality needed in the military to his players. He wasn’t a yeller in meetings; rather, he would get on players, but he wouldn’t scream.

“Once you realized that he did the things he did to keep you on edge, to keep you always thinking, and preparing,” Rivera said. “He was a tremendous, tremendous motivator and coach.”

He also was good at explaining why he wanted something done on a play. Ryan used to stand about 30 yards behind the defense and signal in the calls. Rivera said he wouldn’t talk or yell, so players had to learn — and understand — the signals. Occasionally, Ryan would quiz Rivera — whom he dubbed “Chico” after the main character from the 1970s sitcom “Chico and the Man” — about why they were running a particular defense.

Other times Rivera would ask why they ran a particular look. Ryan would explain the chess moves behind his thinking.

“He always did a great job of giving the why,” Rivera said. “That’s one of the things that I carried, that when I was coordinator I tried to make sure everybody understood why we wanted to do the things that we were doing.”

‘Now you guys have got to go out and do it’

The most famous song-and-dance video by a football team, “Super Bowl Shuffle,” was born in large part because of Bears receiver Willie Gault, who suggested it to a music producer.

But Rivera didn’t participate for the same reason a number of teammates didn’t: The video was shot Tuesday morning — after the Bears had played a Monday night game in Miami. That also happened to be their first loss of the season. Rivera said they left Miami around 1:45 a.m.; the shoot was scheduled for 8 a.m.

“It was an open invite for everybody,” Rivera said.

One rehearsal had taken place on the Saturday before the team left for Miami, so a lot of players already had decided not to attend. Morrissey, who was in the video, also recalled Gault walking down the aisle on the team plane to Miami asking who wanted to participate.

Because the Bears lost, and some players objected to it even before the game, only 24 players attended the video shoot, which took 10 to 12 hours. McMahon and Payton, who agreed to participate, did so later in the week and were inserted into the video.

“When it came out, Ditka told us, ‘All right. Now you guys have got to go out and do it,'” Rivera said.

‘Let’s go run some hills’

Payton loved running hills, a workout that became legendary. He’d run them in the offseason and during camp, using them to stay in shape on days he didn’t practice. That’s how Rivera found himself running a set of 10 hills behind the football stadium at Wisconsin-Platteville.

One day, Rivera wasn’t practicing because of a shoulder injury. After he got treatment, Payton said to Rivera, “Let’s go run some hills.” Rivera had no other choice but to say, “OK.”

Rivera then pointed to an approximate 50-foot hill with perhaps a 20-degree incline outside his Commanders office, and he said the one in Platteville was longer and steeper. Payton always ran 10; that meant Rivera had to do so as well.

“Sure enough, he just started going, and so I start following him,” Rivera said. “It was hard to keep up with him. I mean, the first couple, you’re right there. But after that, he’s going. He’s smoking people. But he did that. That was just his workout. Just one of the most unbelievable people. … He had a tremendous work ethic.”

‘He knew how to test people’

Rivera called McMichael, the one-time defensive tackle and former professional wrestler, a “uniquely clever” guy. Rivera called it Cowboy wisdom. Even now, he said McMichael, stricken with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), remains sharp.

Rivera then relayed his favorite story about a player nicknamed Mongo and Ming.

“We had this young running back from Texas one year, and Ming was wearing him down,” Rivera said. “Every chance he got he would wear this kid down. Ming would hit him and drive him into the ground, and the kid would get up like that, and he’d walk back to the huddle. Ming would say, ‘That’s right. That’s right.’ So then the kid came out one day and Ming had just lit him up and threw him to the ground.

“The kid popped up and pushed Ming. Ming turned around, and he hit Ming. Ming just kind of turned his head real quick because he caught him just on the cheek. He turned his head and he goes, ‘You’re going to be OK now. Just so y’all know, the pup just doesn’t bark, the pup bites. That’s good.’ That was it. He stopped picking on the kid. He knew the kid was going to be all right. He knew how to test people.”

‘I saw the young man go up and dunk the ball at about 325 pounds’

When Chicago drafted Perry, the NFL did not have many 300-pound players. In fact, he was one of perhaps 15 in the NFL who fit in that category. Now? The Commanders have 10 such players on their 53-man roster alone.

He became a household name in 1985 in large part because Ditka used him on offense — and he rushed for two touchdowns that season, and another in the Super Bowl.

“He really did stand alone at times just because of the personality he became,” Rivera said.

But the 325-pound Perry, nicknamed “The Fridge,” wasn’t wanted by Ryan, who called him a wasted draft pick. However, Perry did start nine games as a rookie.

“It was very rare to have a 300-pounder with his athleticism,” Rivera said.

He saw it on the basketball court as well as on the football field.

“I would put my hand on a Bible and vouch for the fact that the guy did dunk,” Rivera said. “I watched. We used to play basketball together. We lived in the same area. We would go to the same sporting club and play basketball together. I’m serious. I saw the young man go up and dunk the ball at about 325 pounds. That was almost unheard of in 1985. I mean, he was a phenomenal athlete, and he was a good person, too. But those were those types of personalities that we had.”