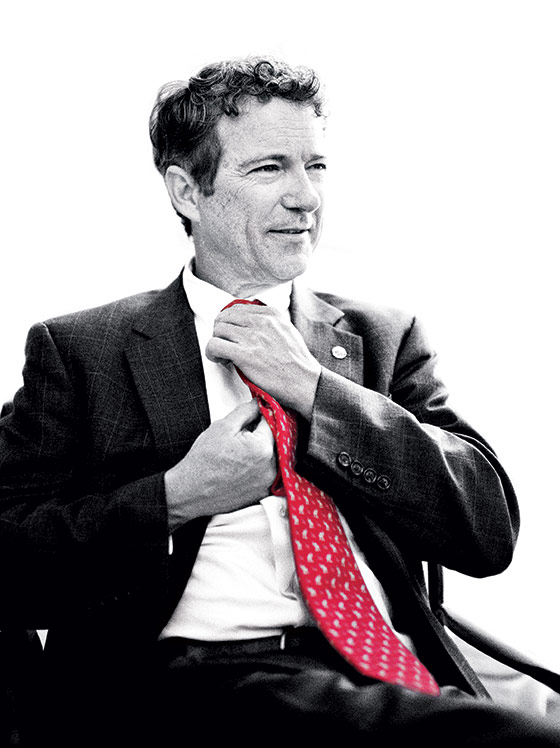

Its Hard to Hate Rand Paul

It’s Hard to Hate Rand Paul

By

Frank Rich,

a writer-at-large for New York Magazine

In the Labor Day weekend scramble set off by President Obama’s zero-hour about-face on Syria, the only visible politician in Washington who knew just what he wanted to say and said it was the junior senator from Kentucky, Rand Paul. Appearing after John Kerry on Meet the Press that Sunday, Paul reminded viewers of Kerry’s famous Vietnam-era locution, then said he would like to ask him a question of his own: “How can you ask a man to be the first one to die for a mistake?”

There were no surprises in Paul’s adamant opposition to a military strike. But after a chaotic week of White House feints and fumbles accompanied by vamping and vacillation among leaders in both parties, the odd duck from Kentucky emerged as an anchor of principle, the signal amid the noise. Paul’s constancy was particularly conspicuous in contrast to his presumed Republican presidential rivals in 2016, Marco Rubio, Paul Ryan, and Ted Cruz. Though each of them had waxed hawkish about Syria in the past—in Rubio’s case, just the week before—they held their fire over Labor Day weekend, stuck their fingers to the pollsters’ wind, and then more or less fell in with Paul’s noninterventionist bottom line once they emerged. It’s not the first time that Paul had proved the leader of the pack in which he was thought to be the joker.

This has been quite a year for Paul. Not long ago, he was mainly known as the son of the (now retired) gadfly Texas congressman Ron Paul, the perennial presidential loser who often seemed to have wandered into GOP-primary debates directly from an SNL sketch. Like his father, Rand Paul has been dismissed by most Democrats as a tea-party kook and by many grandees in his own party as a libertarian kook; the Republican Establishment in his own state branded him “too kooky for Kentucky” in his first bid for public office. Now BuzzFeed has anointed him “the de facto foreign policy spokesman for the GOP”—a stature confirmed when he followed Obama’s prime-time speech on the Syrian standoff with a televised mini-address of his own.

But even before an international crisis thrust him center stage, Paul had become this year’s most compelling and prescient political actor. His ascent began in earnest in March with the Twitter-certified #standwithrand sensation of his

Paul’s charisma is an anti-charisma. He can look as if he’s just gotten out of bed and thrown on whatever clothes he’d tossed on the floor the night before. His voice is a pinched drawl reflecting his Texas upbringing. He is earnest and direct, and not much given to laughter or the other public displays of feeling that stuffy white guys (like Mitt Romney) try to simulate once in the arena. He sometimes comes across like an alien who has dropped down from outer space—and in a figurative sense he is. In both style and substance, he seems a premature visitor from the future American political landscape that Republicans and Democrats alike will inhabit once they no longer have Obama to either kick around or revere. That America may well be as polarized as the one we have now, but with Obama gone (and some or all of the parties’ current leaders in Congress gone as well), the dynamics of our partisan culture will inevitably change. Paul is the only Republican presidential contender out there who seems to get the fact that a time is coming when the first Obama election of 2008 will not be refought over and over again like some infernal Groundhog Day. Democrats who lump him with Sarah Palin, Michele Bachmann, Cruz, and Glenn Beck are still hoping to fight the last war. Paul is an original. He may be the first American senator to approvingly cite both Ayn Rand and Gabriel García Márquez. He has, in the words of Rich Lowry of National Review, “that quality that can’t be learned or bought: He’s interesting.” In that sense, he’s kind of a Eugene McCarthy of the right, destined to shake things up without necessarily reaping the rewards for himself.

Though he has been at or near the top of near-meaningless early primary polling, he is nonetheless a long shot to ascend to the top of the GOP ticket, let alone to the White House. And a good thing too: A Paul presidency would be a misfortune for the majority of Americans who would be devastated by his regime of minimalist government. But as we begin to imagine a post-Obama national politics where the Democratic presidential front-runners may be of Social Security age and the Republicans lack a presumptive leader or a coherent path forward, he can hardly be dismissed. Nature abhors a vacuum, and Paul doesn’t hide his ambitions to fill it. In his own party, he’s the one who is stirring the drink, having managed in his very short political career (all of three years) to have gained stature in spite of (or perhaps because of) his ability to enrage and usurp such GOP heavyweights as John McCain, Mitch McConnell, and Chris Christie. He is one of only two putative presidential contenders in either party still capable of doing something you don’t expect or saying something that hasn’t been freeze-dried into anodyne Frank Luntz–style drivel by strategists and focus groups. The other contender in the spontaneous-authentic political sweepstakes is Christie, but like an actor who’s read too many of his rave reviews, he’s already turning his bully-in-a-china-shop routine into Jersey shtick. (So much so that if he modulates it now, he’ll come across as a phony.) Paul doesn’t do shtick, he rarely engages in sound bites or sloganeering, and his language has not been balled up by a stint in law school or an M.B.A. program. (He’s an ophthalmologist.) He speaks as if he were thinking aloud and has a way of making his most radical notions sound plausible in the moment. It doesn’t hurt that some of what he says also makes sense.

The sum of his credo can be found in his unvarnished new book. Titled Government Bullies: How Everyday Americans Are Being Harassed, Abused and Imprisoned by the Feds, it’s a repetitive catalogue of anecdotes showcasing ordinary citizens and small businesses that have been hounded by idiotic government regulations or bureaucrats or both. The most universal of these horror stories is the one that happened to Paul himself—a Kafkaesque manhandling by TSA airport inspectors that’s bound to hit home with anyone who has passed through security at an American airport. Paul’s other tales of woe are no doubt equally true, and often egregious. The problem is that out of such grievances he builds a blanket case for castrating or doing away with most government agencies and regulations, from his father’s bête noire the Federal Reserve to the Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration (not to mention the requisite three or four Cabinet departments on any right-wing politician’s hit list). So instinctive is his defense of commerce against government interference that he defended BP during the Gulf spill (“Accidents happen”) and condemned the Obama administration for putting its “boot heel on the throat” of the oil giant. It’s the same ideological conviction that led him, in his 2010 senatorial campaign, to revive the self-immolating Barry Goldwater argument that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was flawed by its imposition of racial integration on “private enterprise” like, say, lunch counters.

What separates Paul from many of his tea-party peers is his meticulous insistence on blaming Republicans and Democrats alike for the outrages he finds in every tentacle of the federal Leviathan. He also takes a moderate rhetorical tone, far removed from that of the other right-wing politicians, Fox News talking heads, and radio bloviators who share his views. “I believe no one has the right to pollute another person’s property, and if it occurs the polluter should be made to pay for cleanup and damages,” he writes in one typical passage. “I am not against all regulation. I am against overzealous regulation.” There’s no “Don’t Tread on Me” overkill in his public preachments. He harbors no impeachment fantasies and not so much as a scintilla of Obama hatred even as he leads the charge against what he sees as the oppressive government nightmare of Obamacare. This has been the case from the start. When Paul began running for the Senate, it was during the red-hot tea-party year of 2009, with its tsunami of raucous town-hall meetings and death threats to the president. Paul gladly accepted Palin’s endorsement, but never succumbed to those swamp fevers. Though the liberal editorial page of the Louisville Courier-Journal was dismissive of his views during his Senate race, it went out of its way to observe that the man himself was “neither an angry nor resentful person” and was instead “thoughtful and witty in an elfin sort of way.”

Paul’s opponent in that primary, the Kentucky secretary of State, Trey Grayson, was endorsed by a Who’s Who of the Establishment, from McConnell, the state’s senior senator, to the neocon compadres Dick Cheney and Rudy Giuliani. Polls showed that primary voters favored Grayson’s national-security views over Paul’s by a three-to-one ratio. But Paul won in a landslide, a feat he easily replicated against his Democratic adversary in the general election. Since that rout, the balance of power between McConnell and Paul has reversed.

It’s not every day you see a party’s leader in the United States Senate play sycophant to a freshman two decades his junior. But having failed to stop Paul, McConnell is desperate to be in his good graces as he faces a possible tea-party challenge from the right in his reelection bid next year. This has led him to hire a longtime aide to both Pauls, Jesse Benton, as his campaign manager even though Benton isn’t precisely in awe of his new client: He was caught on tape saying that he was “sort of holding my nose” to take on the assignment, and was doing so mainly because it “is going to be a big benefit for Rand in ’16.” McConnell is holding his own nose over that and much more. He has signed on to Paul’s pet cause of legalizing the farming of hemp for industrial use—a development that would seem as remote as John Boehner’s declaring himself a Dead Head. And to the astonishment of those who regard McConnell as the epitome of Republican orthodoxy, he threw in his lot with Paul on Syria too, becoming the only one of either party’s leaders in either chamber of Congress to oppose intervention.

McConnell’s self-interested stand on Syria is but an addendum to a large and substantive sea change in GOP foreign policy, much of it attributable to Paul. The complacent neocon Establishment has been utterly blindsided. Just ask Bill Kristol, who had predicted that only five Republican Senators would join Paul in opposing military action in Syria—a vote count off by more than 400 percent. And just ask Christie, who attacked Paul’s national-security views this summer from what he no doubt thought was the unassailable political and intellectual high ground—only to find out he had missed the shift in his own party’s internal debate. In retrospect, both the Christie-Paul brawl and its antecedent—the interparty debate that followed Paul’s thirteen-hour homage to Mr. Smith Goes to Washington in March—are signal events in understanding how Paul’s stature and allure keep growing among Republican voters while his rivals seem ever smaller, shriller, and impotent.

What drove Christie to launch a strike was Paul’s fierce response to the latest revelations of NSA domestic snooping. Paul had judged James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, the villain of the case and had compared Edward Snowden’s civil disobedience to that of Martin Luther King and Henry David Thoreau. “This strain of libertarianism that’s going through both parties right now and making big headlines I think is a very dangerous thought,” Christie declared in a forum at the Aspen Institute, and for good measure tossed in 9/11 (“widows and the orphans”) lest anyone doubt that Paul and his ilk were soft on terrorism.

The New Jersey governor spoke with the certainty of a man with good reason to believe the party’s wind was at his back. The Wall Street Journal editorial page had earlier dismissed Paul’s anti-drone filibuster as a “political stunt” designed to “fire up impressionable libertarian kids in their college dorms.” Kristol had mocked Paul as a “spokesman for the Code Pink faction of the Republican Party.” McCain had dismissed him as one of “the wacko birds.” (He later apologized.) And after Christie spoke, the same crowd piled on. The Long Island congressman Peter King likened Paul not just to antiwar Democrats of the sixties but to “the Charles Lindberghs that said we should appease Hitler.” Christie’s Aspen performance was “fearless” and “electrifying,” said the neocon pundit Charles Krauthammer, and “an extremely important moment.”

But not everyone on the right believed Christie had thrown a knockout punch at the infidel within the GOP. Writing in Commentary, Jonathan Tobin noted that other conservatives had been echoing Paul’s condemnation of the “national security state” and accused as unlikely a subversive as Peggy Noonan of defecting to the “old line of the hard left.” Even the ultimate GOP tool, the party chairman Reince Priebus, had praised Paul’s filibuster as “completely awesome.” Tobin worried that a “crack up” of the “generations-old Republican consensus on foreign and defense policy” would be at hand if others didn’t follow Christie’s brave example and stand up to Paul and his cohort before “they hijack a party.”

The truth is that that consensus cracked up long ago—done in by the Bush administration and the amen chorus, typified by McCain, Kristol, and Krauthammer, that led the country into the ditch of Iraq. As Reason, the Paul-sympathizing libertarian magazine, pointed out approvingly, Paul’s filibuster “could have been aimed 100 percent at George W. Bush and the policies the Republican party and the conservative movement have urged for most of the 21st century.” And he had gotten away with it despite the protestations of the old conservative guard. Christie may think he can rewrite or reverse this history by attacking Paul, but he’s in denial. Bellicose exhortations consisting of a noun and a verb and 9/11 reached their political expiration date with the imploded Giuliani campaign of 2008.

Indeed, Paul’s opposition to Bush-administration policies is essentially the same as Obama’s when he rode to his victories over Hillary Clinton and McCain. An Ur-text for Paul’s argument against Syrian intervention can be found in Obama’s formulation of 2007: “The president does not have the power under the Constitution to unilaterally authorize a military attack in a situation that does not involve stopping an actual or imminent threat to the nation.” Like Obama the candidate, Paul was in favor of the post-9/11 war in Afghanistan, against the war in Iraq, skeptical about the legal rationale for Guantánamo, and opposed to the Patriot Act. That’s more or less the American center now. Well before the Snowden NSA revelations, the public was consistently telling pollsters that the federal government was untrustworthy and too intrusive. So low is the public’s appetite for military action abroad that only 9 percent of Americans favored an American intervention in the Syrian civil war in a Reuters survey at the end of August. Once the horrific images of the chemical-weapons slaughter in Damascus became ubiquitous, the percentage of those favoring an American military response still remained well below 50 percent. The more vehemently the strange bedfellows of Obama and the Journal editorial page argued for action—and the more prominently Paul argued against—the more public support fell away. A Journal–NBC News poll taken in the week after Labor Day found that only 44 percent of Americans approved of a limited military strike, and just 36 percent of Republicans.

In response to Christie’s Aspen fusillade, Paul asked why his fellow Republican “would want to pick a fight with the one guy who has the chance to grow the party by appealing to the youth and appealing to people who would like to see a more moderate and less aggressive foreign policy.” After the exchange of barbs died down, Christie retreated. Asked his position on a Syrian intervention after Labor Day, he proved a profile in Jell-O, announcing that he would pass the buck on the issue to the New Jersey delegation in Congress, led by a Democratic nemesis, Robert Menendez. McCain has blinked too. When Paul called for cutting off American aid in response to the generals’ coup in Egypt, McCain condemned him for sending the “wrong message” and making a “terrific mistake”—yet he and other GOP Senate hawks came crawling back to Paul’s position just two weeks later.

Paul’s independence from his party on national-security issues resembles his father’s, but he is careful to sand down the libertarian edges; he refuses to accept the label “isolationist,” calling himself a realist in the George Kennan mode and paying deference to the United Nations Security Council. He sounds more mainstream than his dad, and is. His fear that American missile strikes would serve mainly to pour still more oil on the fires of the Middle East is so prevalent in both parties that it was impossible for the liberal host of CNN’s Crossfire, Stephanie Cutter, to bait him into the hoped-for partisan fisticuffs on the revamped show’s debut episode. Paul can hit a bipartisan sweet spot on occasional domestic issues too. His push to reform mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenders brought him an alliance with the liberal Democratic senator Patrick Leahy and has now been belatedly embraced by the attorney general, Eric Holder.

None of this means that Paul has any serious chance of appealing to centrist and liberal Democrats in significant numbers in a national campaign. He labors under most of the same handicaps as the rest of his party. He has no credible commitment to serious immigration reform. He is an absolutist on guns and abortion. He is opposed to gay marriage (though trying, like many Republicans these days, to keep the issue on the down-low). In a speech at the Reagan Library this year, he acknowledged that the Republican Party will not win again until it “looks like the rest of America,” but his own outreach efforts have been scarcely better than the GOP’s as a whole. His game appearance at the historically black Howard University backfired when he tried to pretend that he had never “wavered” in his support of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 even though his recent wavering was a matter of public record, captured on video.

While Paul has tried to stay clear of the loony white Christian-identity extremists who gravitated to his father, he had to sacrifice an aide who was recently unmasked as a onetime radio shock jock prone to neo-Confederate radio rants under the nom de bigot “Southern Avenger.” What was most interesting about the incident, however, was the response of another cardinal of the waning GOP Establishment, the George W. Bush speechwriter turned Washington Post columnist Michael Gerson, who argued that Paul’s harboring of the Southern Avenger illustrates why it is “impossible for Rand Paul to join the Republican mainstream.” By that standard, the party would also have to drum out Rick Perry, who floated the fantasy of Texas’s seceding from the union, along with all the other GOP elected officials nationwide who are emulating Perry’s push for voter-suppression legislation in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s vitiation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. That Gerson would hypocritically single out Paul for banishment in a party harboring so many southern avengers is an indication of just how panicked the old GOP gatekeepers are by his success. They will grab anything they can find to bring him down.

And they will keep trying. As a foe of the bank bailout of 2008 and the Fed, Paul is anathema as much to the Republican Wall Street financial Establishment as he is to the party’s unreconstructed hawks. Those two overlapping power centers can bring many resources to bear if they are determined to put over a Christie or Jeb Bush or a Rubio—though their actual power over the party’s base remains an open question in the aftermath of the Romney debacle. What’s most important about Paul, however, is not his own prospects for higher office, but the kind of politics his early and limited success may foretell for post-Obama America. He doesn’t feel he has to be a bully, a screamer, a birther, a bigot, or a lock-and-load rabble-rouser to be heard above the din. He has principled ideas about government, however extreme, that are nothing if not consistent and that he believes he can sell with logic rather than threats and bomb-throwing. Unlike Cruz and Rubio, he is now careful to say that he doesn’t think shutting down the government is a good tactic in the battle against Obamacare.

He is a godsend for the tea party—the presentable leader the movement kept trying to find during the 2012 Republican freak show but never did. Next to Paul, that parade of hotheads, with their overweening Obama hatred and their dog whistles to racists, nativists, and homophobes, looks like a relic from a passing era. For that matter, he may prove equally capable of making the two top Democratic presidential prospects for 2016, Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden, look like a nostalgia act.

This leaves Paul—for the moment at least—a man with a future. If in the end he and his ideas are too out-there to be a majority taste anytime soon, he is nonetheless performing an invaluable service. Whatever else may come from it, his speedy rise illuminates just how big an opening there might be for other independent and iconoclastic politicians willing to challenge the sclerosis of both parties in the post-Obama age.

It’s Hard to Hate Rand Paul