Most Precise Atomic Clock Ever Built Will Only Lose a Second Every 30 Billion Years

New clock just dropped, but it’ll only drop a second every 30 billion years while in operation. That’s right: It’s the most precise, accurate clock yet built.

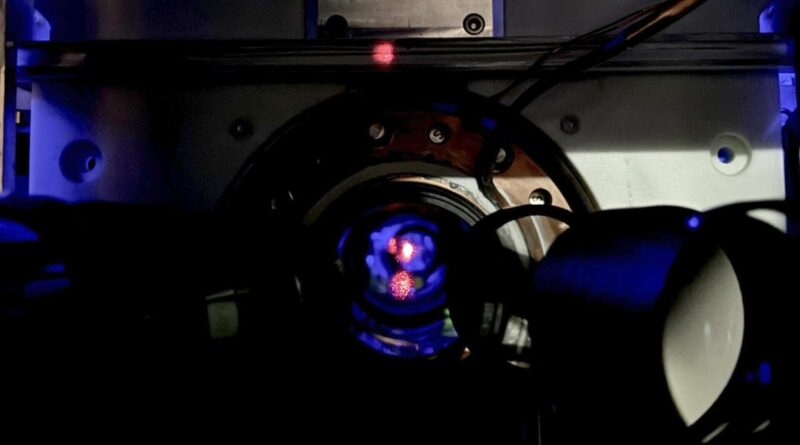

The timekeeping device was developed by scientists at JILA, a joint institution of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado Boulder. It is effectively an atomic trap, which keeps tens of thousands of atoms in place and measures time through the reliable movement of electrons around the atom. The clock is described in a not-yet-peer-reviewed paper currently hosted on the preprint server arXiv.

The standard second is established based on the cesium atom, but the new clock uses supercooled strontium atoms to keep track of time. As reported by ScienceAlert, the new clock is twice as accurate as the previous timekeeping record holder.

“This clock is so precise that it can detect tiny effects predicted by theories such as general relativity, even at the microscopic scale,” said NIST and JILA physicist Jun Ye, co-author of the recent study, in a NIST release. “It’s pushing the boundaries of what’s possible with timekeeping.”

As described in Einstein’s theory of general relativity, time itself is affected by gravity. The newly invented clock can detect relativistic effects on its timekeeping; in other words, if the gravitational field around the clock changes, the clock will, uh, clock that. Gravity’s effect on time will be a significant factor once NASA and its partners implement a separate time zone for the Moon; this effect causes lunar clocks to run 58.7 microseconds faster each day compared to those on Earth.

As humankind ventures to distances much farther than the Moon, precise atomic clocks will be crucial to help space agencies navigate the cosmos without error. The methods used to control the supercooled atoms can also be used in quantum computers, which use atoms near absolute zero as bits (called “qubits”) for their operations.

“We’re exploring the frontiers of measurement science,” Ye said. “When you can measure things with this level of precision, you start to see phenomena that we’ve only been able to theorize about until now.”

The average atomic clock today operates at microwave frequencies, NIST states, but strontium atomic clocks operate at optical frequencies. It “ticks” trillions of times per second, and is accurate to within 1/15,000,000,000 of a second per year. Only losing a second every 30 billion years means that if such a clock started ticking at the beginning of the universe, the universe would still need to be more than twice its current age for the clock to lose a second.

Staggering stuff, and perhaps as good a reminder as any that time is of the essence. Why are you still reading? Go enjoy life.

Correction: A previous version of this post gave the incorrect value for how much faster a clock needs to run on the Moon relative to Earth. It’s 58.7 microseconds, and not nearly an entire second.

More: Gizmodo Monday Puzzle: I Bet You Can’t Tell Time on This Warped Clock