Morocco’s unique cave dwellings attract tourist

This is Bhalil – a small, traditional town near Fez in Morocco.

All who enter it are welcomed with an enormous “I love Bhalil” sign fixed onto the town’s only major roundabout. And it’s easy to understand why – for behind Bhalil’s ordinary looking buildings lie hidden gems.

Bhalil is one of the most unique hillside towns in Morocco, thanks to its historic cave houses.

Dating back to the fourth century, the caves were first inhabited by the Amazigh, then by the Volubilis, followed by the Banu Hilal in 1270.

Nowadays, the caves – many of which are still inhabited by locals – are a tourist attraction, pulling in visitors from all over the world.

Thami Anjam is a cave owner and president of Bhalil’s Association for Tourism, Culture, Environment and Sport.

“These caves were formed by the valleys, which made a group of people settle here, and the criteria that encouraged them to settle, first the height, as the town is located in the mountains, in addition to the abundance of water and fertile soil,” he says.

Bhalil’s has an abundance of water and flowing springs – the area includes about 600 caves and 45 water sources.

“When people came to live here, and found several holes or caves, they dug more in order to provide either a private residence for the family or animals or also to store the agricultural crop. When they settled here, they added several elements to the caves in order to absorb moisture, for example lime, clay or hay,” explains Anjam.

Over the years, the growth of the town lead to its development, with modern homes outnumbering the cave dwellings.

Anjam doesn’t live in his cave house. Instead he’s opened it up for tourists to visit and stay in.

His neighbour, Najia Sribet, still lives in her cave, but allows tourists to visit as part of the guided tours on offer in the town.

“I inherited this cave from my father, and we remained settled here because we did not have the money to buy a house, so we decided to stay here,” says Sribet.

While the caves have been transformed into comfortable homes, there is a downside to living inside a rock formation so close to water sources.

“The difficulties we suffer from in the cave are the humidity, so it must be cleaned constantly, we really suffer here but we have nothing to do,” Sribet explains.

Despite the challenges, Anjam and other cave owners are doing their best to keep the dwellings looking their best.

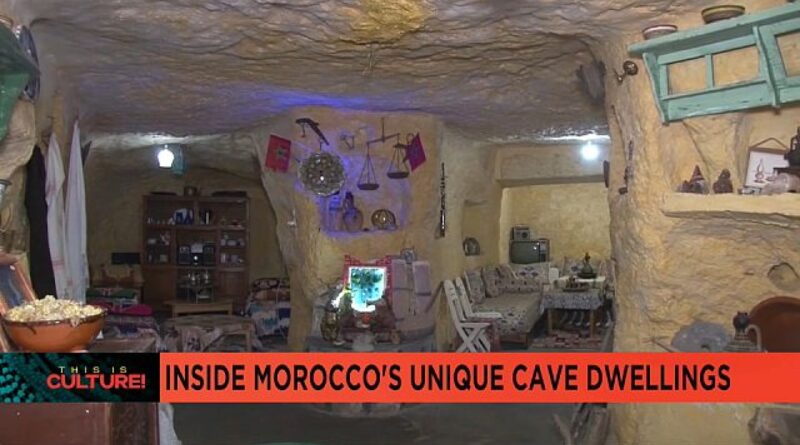

Some have been equipped to suit the needs of tourists, and have had electricity and running water installed.

Anjam’s cave has chic furnishings and even a telephone line.

“The caves contribute to attracting foreign tourists from all over the world. Tourists are amazed when they enter the cave and find themselves in a unique place of its kind,” says Anjam.

In total there are 6 tourist caves and since 2021, Bhalil has received between 200 to 300 tourists per year, according to the Bhalil Association for Tourism, Culture, Environment and Sport.

“Tourism in the region benefits all the local workforce but at the same time there are a number of challenges we are faced,” says Anjam.

The cave dwellings are quickly vanishing as Bhalil’s inhabitants prefer to live in more modern housing.

There’s clear difference between the caves that have been prepared to receive tourists and those that are still used as housing for locals.

While tourist caves are often equipped with facilities that ensure the comfort of visitors, other caves lack such amenities.

The Bhalil Association for Tourism, Culture, Environment and Sport hopes government funding will be provided for cave restoration to preserve the traditional heritage of the dwellings, which is an essential part of the identity of the local population.

Additional sources • AP