What Goes into Building the Idea of ‘Modi, the Supreme’?

In one of his interviews held in 1977, the French philosopher Michael Foucault has made an interesting observation on the inextricable relationship between the body of the King and question of sovereignty in 17th century Europe. To paraphrase Foucault’s words: as kings physically personified nations in the early modern period, the King’s body was then not a metaphor, but a political reality, the physical presence and protection of which was necessary for the functioning of monarchies. The survival of monarchies depended to a great extent on protection of the body of monarch in a juridical-political sense.

Modern democratic revolutions brought about a change in the situation. Though many thought of it as a utopian idea initially, it soon emerged as the new corporeal political entity that needed to be protected using both ideological and coercive measures. Modern constitutions were introduced with the purpose of legitimising the supremacy of people or nations and their right to exercise national sovereignty.

The idea of sovereignty prevailed in the early modern period linking it with the body of ruler as a corporeal reality appears to be regaining popularity in the current political discourse in India. There is, of course, a point in paraphrasing Foucault at a time when attack on Prime Minister Narendra Modi by the BBC is being perceived as an attack on the body of Indian nation.

The issue also invokes a serious question; why the re-emergence of ruler’s body as a corporeal political entity in a democratic country like India is a dangerous one.

Seeing Political Critique as an ‘Attack’

The first set of responses to the BBC documentary from the Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP) and the government of India came in the way of painting it “vile propaganda” undermining “the sovereignty and integrity of India.”

These responses understandably reflect the government’s fear that the BBC documentary had the potential to adversely impact India’s image among the international comity of nations and its cordial relations with other countries. But beyond such a fear or concern, the Government’s decisions to ban the documentary from being aired in India, to intimidate BBC by raiding its offices in Delhi and Mumbai and to order YouTube and Twitter to block any content related to the documentary from being published on their platforms, all echoes a new sovereignty debate in circulation – presenting any critique of the prime minister as something tantamount to an unbearable attack on India’s national sovereignty.

Strangely enough, in its response to the Hindenburg Report, the Adani group has also resorted to the same set of tactics terming the move a “calculated attack on India, the independence, integrity and quality of Indian institutions, and the growth story and ambition of India.”

Idea of ‘Supreme’ Political Authority and ‘Sovereignty’

In order to make sense of the issue, one must first take a look at the political backdrop that the ideas of supreme political authority and sovereignty emerged in India. This entered political discourse arguably as a product of Indian National Movement. The evolution of it was adherence to the modern European phenomenon, the British to be more specific, but it remained very Indian in scope and content because of the peculiar historical context in which its evolution took place. It also facilitated a postcolonial transition from the British Monarch as allodial power to the Parliament as the sole source of law within the land.

Even for Gandhi, who had otherwise been critical of most political ideals of modern European origin for their alleged hostility towards humanity, popular sovereignty in its Indian avatar did not seem problematic. Instead, his perspective assumed that there is an importance of the idea of popular sovereignty as it promotes individual liberty and personal autonomy to a higher extent. Gandhi actually encouraged reimagining sovereignty as something politically away from the realm of the nation or state.

The idea of popular sovereignty and the extent of sovereign power to the people of India, thus, became central to the spirit of Indian constitution.

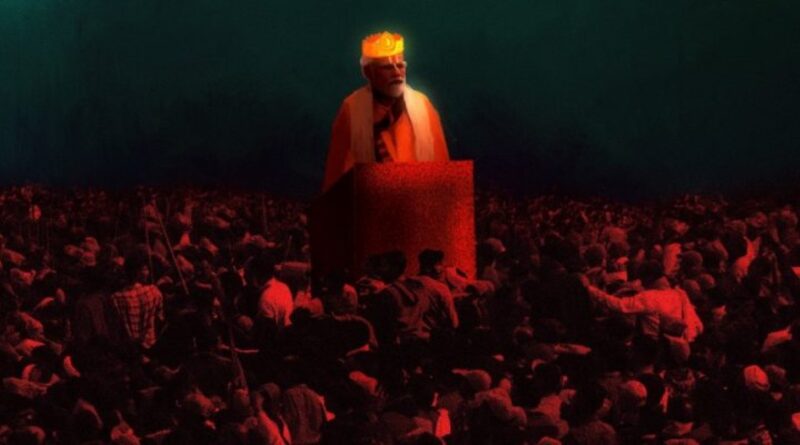

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

Nonetheless, sovereignty as a political notion in India has always been a contested concept gathering meaning not solely from the postcolonial sense of the term. It sometimes operates as a parochial nationalist construct. We have experienced this manifestation of sovereignty during the National Emergency (1975-77), when Indira Gandhi used threat to national sovereignty as a pretext to consolidate and exercise coercive power. Lately, on several occasions, the concern over national security and sovereignty has become instrumental for legitimising the act of using excessive powers by the state.

The current events in Indian politics demonstrate how a sovereign, an incarnation of the European kings of the 17th century with attributes of ‘legal impunity’, ‘unquestionable rights’ and ‘unattackable persona’ is being resurfaced in varying ways. There is a predictable pattern of events unfolding and taking the nation towards a debate on alternative sources of sovereignty and the question where the supreme authority actually resides in.

This is not just a legal issue but an issue entailing a serious political crisis- a populist leader or a party claiming to exercise the sovereignty of the people. How far Modi himself or his party has succeeded in making himself or itself the sovereign is a different question altogether, but a large section in the India media subtly endorses his new stature without any reservations or ideological hassles.

Colonial?

It is also interesting to note that while responding to the BBC expose, Arindam Bagchi, the spokesperson of Ministry of External Affairs, lashed out at the broadcaster of maintaining a political agenda and lambasted the BBC production as a “propaganda piece” made with a “continuing colonial mind-set.”

The choice of invoking “colonial” as the frame of discourse by the government, the Prime Minister and the BJP is an intentional one effectively serving an immediate political purpose. Right from the beginning of his tenure as the Prime Minister of the nation, Modi presents himself as a postcolonial liberator, presuming that he is the one who will liberate the people of India from ill-effects of colonialism that both the ‘Muslim’ Mughals and ‘the Christian’ British rule caused.

Also read: No Matter What it Says Now, RSS Did Not Participate in the Freedom Struggle

The creation of a feeling of perpetual ‘colonial victimhood’ and the promise of liberation from it, all seems to form part of the revenge that Modi pretends to engage in since his ascendance to the post of Prime Minister in 2015. His communication is designed well in sync with that with an amalgam of anti-colonial rhetoric, insults, jokes, complaints, threats etc. Modi could also convince a large section of the population that his regime heralded a new era-which many ‘nationalist heroes’ imagined prior to him but failed to achieve.

Modi’s Effective Communication

The other thing that serves to help make Modi ‘the supreme’ is his communication. Whether it is Mann Ki Baat, the regular radio programme hosted by him or his occasional address to the nation, it radiates a sense of power that he delegates to himself from an assumed position of sovereign. Modi skillfully designs his speeches making them more appealing to a large section of population, tradition-oriented and largely skeptical of modernity and developments in science. His communication, a mix of angry, funny gestures, sarcasms and allusions undermines science and ridicules or belittles scientists and scholars.

What is more interesting is how the intellectuals respond to the de-legitimization of science and rationality. They brand it ‘unscientific’ or ‘illogical’ while each of Mod’s seemingly ‘irrational’ remarks such as the statement on the existence of cosmetic surgery and reproductive genetics in ancient India and examples of Ganesha and Karna to support that, find many takers in the Indian society.

As what the Paraguayan dictator Jose Gasper Rodriguez Francia does in Augusto Roa Bastos’ historical novel I the Supreme, Modi constantly ignores the people who find something illogical in it as his speeches are presented to the masses, as ‘wise teachings’ of the ‘Supreme’. That selective warmth towards some and indifference to others in communication is what actually makes him more popular and a favourite amongst a sizeable section of people.

This relationship between “the supreme” and “We the people” who produced him/her being developed through effective act of speech is unfortunately seldom addressed or understood in the Indian context.

M.H. Ilias is a Professor at the School of Gandhian Thought and Development Studies, Mahatma Gandhi University.

A version of this piece was first published on The India Cable – a premium newsletter from The Wire & Galileo Ideas – and has been republished here. To subscribe to The India Cable, click here.