What I Learned From a Hermit Who’s Lived in a Remote Scottish Cabin for 40 Years

Books

Alone and Unafraid

What can we learn from the life of a hermit?

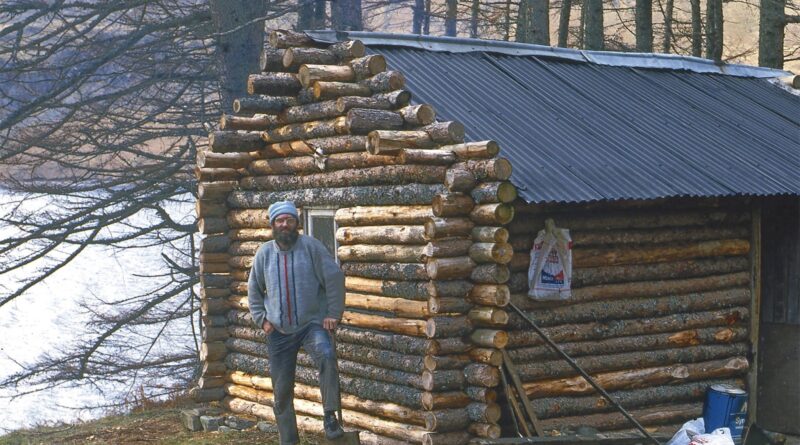

Courtesy of Ken Smith

In Tom Stoppard’s play Arcadia, a rich noblewoman named Lady Croom is having the grounds of her estate redone by the 1809 version of a trendy landscape architect. He wants to add all the artificially wild, lonely, and picturesque touches so popular at the time, including, to her exasperation, a hermitage. The architect suggests that Lady Croom hire a hermit (an actual job position in those days) to live in it by taking out an ad in the newspaper. “But surely,” Lady Croom replies, “a hermit who takes a newspaper is not a hermit in whom one can have complete confidence.”

Who is a hermit in whom one can have complete confidence? Even today we maintain the residual belief that voluntary isolation promotes spiritual or moral insight, thanks to the long history of religious ascetics like the early Christian anchorites—who were walled up alive in small cells attached to churches to spend their lives in contemplation. The professional hermits of Lady Croom’s time were expected to renounce creature comforts, dress in druidic garments, and offer wise counsel to the occasional visitor. In one instance, such a hermit was fired by his employer after he was caught drinking in the local pub. We expect our hermits to be unworldly. Otherwise, how can they be expected to advise us on how to get along in the world?

Sign up for the Slate Culture Newsletter

The best of movies, TV, books, music, and more, delivered to your inbox.

Ken Smith, an Englishman in his 70s who has lived for 40 years in a cabin he built in a remote corner of the Scottish Highlands, may be the most famous living hermit in Great Britain. The subject of a 2022 BBC documentary and now the co-author of The Way of the Hermit, a winning new autobiography written with journalist Will Millard, Smith presents an conundrum. In many respects he fits the eremitic bill perfectly. He lives off the grid, beside a deep loch, miles from other human habitations. He forages, grows, and fishes most of his food, and his only fuel is the wood he chops himself. Smith does not drive and has never used a computer, let alone the internet. He does not take the newspaper.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page.

Thank you for your support.

Yet The Way of the Hermit feels qualitatively different from other hermit-related books, whether the canonical—Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, natch—or lesser-known works: Howard Axelrod’s powerful 2015 memoir of two years spent alone in a Vermont farmhouse, The Point of Vanishing, or third-person reportage like Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild, the story of a young man who abandoned all his possessions on a vision quest to live off the land in the Alaskan bush and died there. Firstly, Smith was far more successful at this enterprise than any of those other guys, none of whom even sniffed his 40-year benchmark. He also seems much healthier emotionally.

Above all, reading The Way of the Hermit throws into relief how angry—overtly or tacitly—most eremitical memoirs are. Thoreau and his heirs focus more on what they dislike about and reject in civilized society than Smith does, whether it’s Thoreau deploring our lives of quiet desperation or simply the buzz of other people’s feelings and opinions from which Axelrod sought relief in complete solitude. Smith comes across as remarkably well adjusted and sweet-tempered, with a good sense of humor regarding his own shortcomings and a generous spirit toward his neighbors (if someone living 20 miles away can be called a neighbor). “I quite like most people,” Smith writes, which is a sentiment one does not pick up from Thoreau. “I am no stranger to a pint or two at the pub either,” he adds, evincing a quality that would have disqualified him from one of those ornamental hermit gigs 300 years ago.

Smith has a better case for misanthropy than most of his hermit predecessors. At the age of 26, while walking home from a disco one night, he was jumped and savagely beaten by a gang of skinheads, for reasons unknown. His injuries were so severe he required four brain surgeries and lay in a coma for two weeks. When Smith regained consciousness, he writes, “not only could I not walk or speak, but I’d also lost two-thirds of my memory and could not write.” His recovery was long and grueling, but it also taught him the power of his own self-discipline and focused his attention on what really mattered to him.

One distinction between Smith and his literary-hermit forebears comes down to class. Smith grew up in a poor, working-class family in northern England; his childhood home had no running water. He left school at 15 to work for the forestry service and then in a series of often dangerous construction jobs. On one site, he fell “thirteen feet from a steel post onto a bed of industrial steel spikes”—none of which, fortunately, pierced a vital organ. As he saw it, he could spend his existence in “my predestined place in the lifelong tradition of earning little whilst giving over my body, mind and most of my time to paying rent and bills,” or he could work equally hard to attain near-complete independence, surrounded by nature. A pragmatic decision indeed. Smith so adores the natural world and enjoys surmounting the challenges required to survive in it that the sometimes daunting Scottish winters feel like a reasonable trade-off.

While there’s a bit of philosophizing in The Way of the Hermit, these passages feel out of place and betray the hand of Smith’s co-author. Smith seems most present in rollicking stories about almost colliding with a grizzly bear on a mountain trail in Canada or hooking a 12-pound ferox trout, a sort of mutated brown monster grown to enormous size in the black depths of the loch. (You can imagine these stories killing at the pub.) When Ken Smith wants to impart some wisdom, it’s invariably about a practical matter, like how to lay a fire so that you get the most heat from the least amount of wood, or how to make wine out of birch sap. (Smith has made wine from a dizzying array of foraged materials, ranging from holly to horseradish to pansies, and he has stocked up gallons of the stuff to be served at his funeral.) He wants his readers to know that wild animals are much less of a threat in the bush than simple exhaustion and exposure.

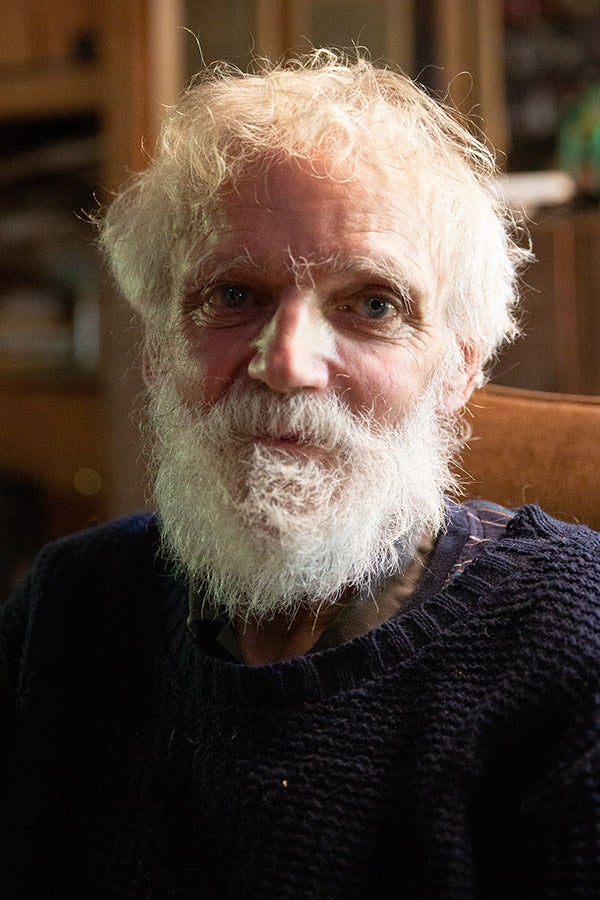

Will Millard

Above all, Smith warns: “If you’ve got somewhere you must be before nightfall, and you are all alone in the wilderness, especially if the weather is bad: DO NOT STOP.” You will quickly become chilled and possibly disoriented. Granted, most of us don’t have to walk 20 miles home from the store or the pub. “I chose a unique way of life,” Smith admits, “which has meant there have been times where I’ve simply had to go out in bad conditions, but that will most likely never be you.” If by some chance, however, that is you, do keep Smith’s preeminent survival tip in mind.

This is probably not the sort of insight that the likes of Lady Croom would have expected from her hermit. And yet Ken Smith is a hermit in whom it is possible to have complete confidence, more so than many others who have picked up a pen (literally, in Smith’s case, since he also doesn’t own a typewriter). Without a doubt, I believe that the primary objects of Smith’s thoughts are matters like how to keep the pine martens from getting at his food stores, whether the roof will hold in the coming storm, and the never-ending task of keeping up his supply of firewood. “Honestly,” he writes, “I think that constant engagement is one of the main attractions for people who choose to live this way.” Cumulatively, these humble doings feel more profound in their fashion than Thoreau’s musings on the Bhagavad Gita and other highfalutin thoughts. They are the basic stuff of existence, the point at which Smith makes daily, intimate contact with the natural world and his own human needs. His ability to appreciate them despite their repetitious quality is worthy of a zen monk.

Given how plainspoken most of the book is, it’s a surprise that Smith’s recounting of a bout with cancer that had him in and out of the hospital before he could finally return home becomes so moving. Smith’s acceptance of his own mortality has an enviable lightness. “Let my body give a good feed to the Highland worms,” he writes. “I have led the life I wanted to live and, no matter what happens now, I can depart this earth a deeply satisfied man.” Few of us can say as much, and it feels like a blessing to have spent this time with someone who can.

-

Slate Book Review

-

United Kingdom

-

Nature